As touch-screen voting systems come online, Aviel D. “Avi” Rubin has been warning of their vulnerabilities—and of threats to the Internet.

notes computer scientist Avi Rubin about the hackers.

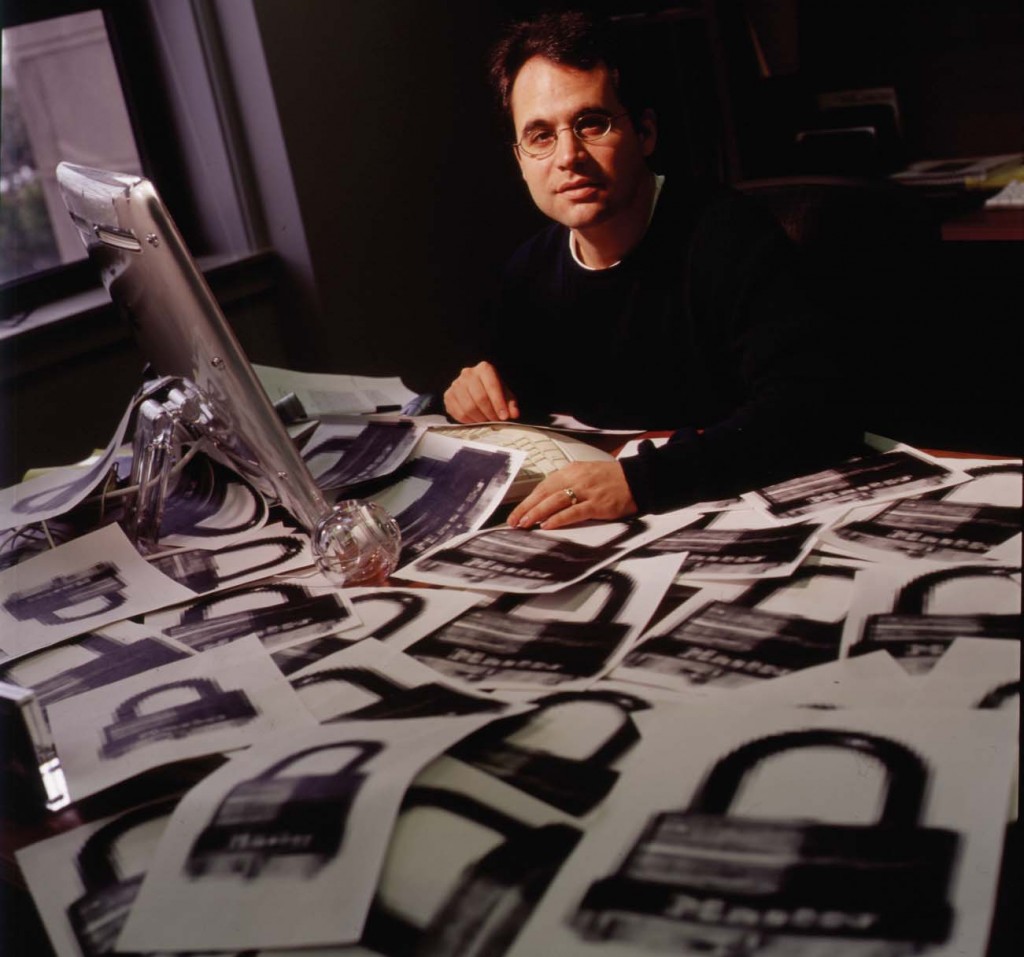

For someone passionate about preserving the public’s privacy, Aviel D. “Avi” Rubin sure hasn’t had a low profile lately. In fact, the technical director of the Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute (ISI) could hardly be more visible. He has been in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, on CNN and NBC, on blue-ribbon commissions reporting to Congress and the White House. His warnings have been splashed across newspaper pages nationwide. He’s hardly had time for his other loves: pool, piano, chess, and sports.

Rubin has been in a very public debate with election officials over the wisdom of implementing new touch-screen voting systems that, according to the computer scientist, can be easily compromised.

Everyone, apparently, has heard of Avi Rubin, who is also professor of Computer Science at the Whiting School of Engineering. Type in his name, and an Internet search returns more than 26,000 references. He’s regularly asked to contribute to online discussions of privacy, security, and computer voting. He was honored with a 2004 Electronic Frontiers Foundation Pioneer Award for “spearheading and nurturing the popular movement for integrity and transparency in modern elections.” In 2001, he received the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for the Best Circumvention of Censorship, based on the Publius anonymous Web publishing system he created. In 2002, he was invited to testify before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China on the subject of web censorship.

Rubin received his BS, MSE, and PhD (1994) in computer science from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He spent several years at AT&T Laboratories, where he was a principal researcher working in cryptography, network security, web security, and secure Internet services. He was also an adjunct professor at New York University. He has authored or co-authored several highly regarded books on computer and Internet security, including White-hat Security Arsenal, Peer-to-peer, and Firewalls and Internet Security, Repelling the Wily Hacker.

The Institute, funded by government agencies and corporations, has a mission “to explore ways to improve existing computer security systems and to design more secure systems,” Rubin explains. A new master’s degree program in Security Informatics at Hopkins will advance the Institute’s educational mission as it helps educate rising generations of information security specialists.

Much of Rubin’s research focuses on the fact that “As more systems rely on the Internet, we become more vulnerable,” he says. “If the Internet goes away, these systems can’t function properly. And it could go away.”

Case in point: In 2003, in what Rubin categorizes as probably the most spectacular assault on Internet security, eight of the 13 Domain Name Servers (DNS), which together comprise the primary routing system for the entire Internet, were “taken down” in a malicious attack. Had all 13 been compromised, the result would have been to eliminate entirely Internet communications, upon which much of the U.S. infrastructure now depends. According to Rubin, “attacks are getting more sophisticated.”

A related topic of concern and research for Rubin and the Institute is the integrity of the Border Gateway Protocol, or BGP. Domain Name Servers use this protocol to make continuous instantaneous decisions about where to route data packets. “The two most vulnerable components of the Internet are the DNS and BGP,” he explains. The Institute, funded through a National Science Foundation grant, is exploring ways to make the BGP more robust.

Privacy and security meet in the voter’s booth. And, it is largely this issue—electronic voting systems—that has given Rubin such a high profile. In the aftermath of the contested 2000 presidential election, Rubin points out, “The Help America Vote Act appropriated just short of $4 billion to upgrade voting machines. So companies started scrambling to provide new machines without anyone saying anything about security.”

Several states, including Maryland, purchased the Diebold touch-screen voting machine system. Rubin contends that “this voting system is far below even the most minimal security standards applicable in other contexts.” The Hopkins researchers issued their findings in a technical report, Analysis of an Electronic Voting System (Information Security Institute, July 2003). This report has generated considerable interest. Many officials maintain that the electronic voting systems they have purchased are secure. Computer scientists and other critics counter that hackers could rig the machines to record votes any way they choose—without detection.

With a few exceptions, Maryland’s touch-screen machines functioned well in their debut in the state’s primary election on March 2. Rubin, who served as an election judge in Baltimore County, told the Washington Post afterward that “some of my concerns were laid to rest and some were made worse.” (For his own account of “one of the most incredible days in my life,” visit avirubin.com/judge.html .)

When asked what connection there is between Internet security and voting, Rubin replies flatly, “Hopefully, none. Unfortunately, some people think the next big thing is voting over the Internet. It is a very bad idea. Current computers aren’t up to it. The Internet is not up to it.

“Our research showing how insecure the machines are is ammunition for the argument that a piece of paper should be part of the system,” he contends. A private, secure paper trail, such as a backup paper ballot, “makes tampering much harder and serves as a check on how the voter voted.”

Rubin was co-author of a study made public in January that warned against the potential for cyber-attacks in the Pentagon’s planned pilot study of Internet-based voting for some military personnel and U.S. citizens living abroad (www.servesecurity report.org).

How does Rubin see the work of the Institute helping solve the problems of information security? “This is what we are all about. We look at all the problems of information security with a strong bias toward preserving privacy,” he says. “If we ignore privacy, we will lose it.”

Visit the Information Security Institute at www.jhuisi.jhu.edu