Cells are remarkable multitaskers, constantly tuning in to their surroundings. While chemical signals often grab the spotlight, physical forces—from stretching and compression to the pressure of blood flow—help keep cells balanced, mobile, and capable of repair. Scientists have long sought to understand how cells detect and respond to these forces, a process that would explain how our bodies adapt and heal.

A team that included researchers from Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, and School of Medicine discovered that when cells are under stress, tiny molecular machines called contractility kits (CKs) spring into action. These protein complexes that help cells adapt to mechanical stress gather at vulnerable spots to reinforce the cells’ structure against potentially damaging forces.

The team’s work, “A Continuum Model of Mechanosensation Based on Contractility Kit Assembly,” appears in Biophysical Journal.

“Our study provides better insights into how cells sense and adapt to physical changes, an ability crucial for processes like wound healing and immune responses,” said study co-author Pablo Iglesias, a professor in the Whiting School of Engineering’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “Understanding how these cellular sensors work could lead to new treatments for diseases like cancer or fibrosis, where cells often fail to respond correctly to mechanical forces. By targeting CK-related proteins, future therapies might restore normal cell behavior, resulting in more effective therapies.”

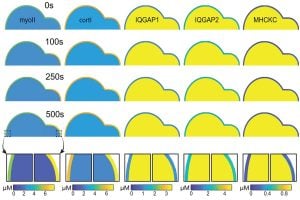

To better understand how CKs work, the researchers created a computational model based on experiments with Dictyostelium cells—simple organisms often used in biology because their cells share similar features with human cells. The model simulates how CKs form, move, and assemble when the cell is under stress. It revealed that CKs are always present inside the cell, ready to act. When stress occurs, CKs rush to the affected area, bringing proteins to support the cell’s structure.

“Our research showed that CKs are essential for handling stress,” said Iglesias. “In addition, we found that cells missing specific proteins, like cortexillin I, struggled to adapt, while cells with too much of certain proteins, like IQGAP1, also did not function well because their CKs could not assemble properly. This demonstrates that a proper balance of proteins is key for CKs to help cells handle stress. CKs also play a role in organizing other proteins, like myosin II, ensuring the cell strengthens in the right areas to manage stress.”

Study co-authors include David Dolgitzer, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University; Alma I. Plaza-Rodríguez, Mark Allan C. Jacob, Bethany A. Todd, and Douglas N. Robinson from the School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University; and Miguel A. Iglesias from Princeton University. The paper was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).