Clearing your cookies is not enough to protect your privacy online.

New research, “The First Early Evidence of the Use of Browser Fingerprinting for Online Tracking,” conducted by a team at Johns Hopkins and Texas A&M universities found that websites are covertly using browser fingerprinting—a method to uniquely identify a web browser—to track people across browser sessions and sites.

“Browser fingerprinting has long been a known privacy threat, but we lacked definitive evidence that it was being used for actual tracking until now,” said co-author Yinzhi Cao, an associate professor of computer science at the Whiting School of Engineering, the technical director of the Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute, and an instructor in the Engineering for Professionals’ computer science program.

When you visit a website, your browser shares a surprising amount of information, like your screen resolution, time zone, device model, and more. When combined, these details create a “fingerprint” that’s often unique to your browser. Unlike cookies—which users can delete or block—fingerprinting is much harder to detect or prevent. Most users have no idea it’s happening, and even privacy-focused browsers struggle to fully block it.

“Think of it as a digital signature you didn’t know you were leaving behind,” explained co-author Zengrui Liu, a former doctoral student in the lab of study co-author Nitish Saxena, professor of computer science and engineering and associate director of the Global Cyber Research Institute at Texas A&M. “You may look anonymous, but your device or browser gives you away.”

The team said that this research marks a turning point in how computer scientists understand the real-world use of browser fingerprinting by connecting it with the use of ads.

“While prior works have studied browser fingerprinting and its usage on different websites, ours is the first to correlate browser fingerprints and ad behaviors, essentially establishing the relationship between web tracking and fingerprinting,” said Cao.

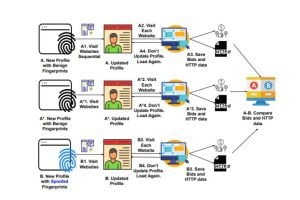

To investigate whether websites are using fingerprinting data to track people, the researchers had to go beyond simply scanning websites for the presence of fingerprinting code. They developed a measurement framework called FPTrace, which assesses fingerprinting-based user tracking by analyzing how ad systems respond to changes in browser fingerprints. This approach is based on the insight that if browser fingerprinting influences tracking, altering fingerprints should affect advertiser bidding, where ad space is sold in real time based on the profile of the person viewing the website, and HTTP records—records of communication between a server and a browser.

“This kind of analysis lets us go beyond the surface,” said co-author Jimmy Dani, Saxena’s doctoral student. “We were able to detect not just the presence of fingerprinting, but whether it was being used to identify and target users—which is much harder to prove.”

The researchers found that tracking occurred even when users cleared or deleted cookies. The results showed notable differences in bid values and a decrease in HTTP records and syncing events when fingerprints were changed, suggesting an impact on targeting and tracking.

Additionally, some of these sites linked fingerprinting behavior to backend bidding processes—meaning fingerprint-based profiles were being used in real time, likely to tailor responses to users or pass along identifiers to third parties.

Perhaps more concerning, the researchers found that even users who explicitly opt out of tracking under privacy laws like Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation and California’s California Consumer Privacy Act may still be silently tracked across the web through browser fingerprinting.

Based on the results of this study, the researchers argue that current privacy tools and policies are not doing enough. They call for stronger defenses in browsers and new regulatory attention on fingerprinting practices. They hope that their FPTrace framework can help regulators audit websites and providers who participate in such activities, especially without user consent.

This research was presented at the 2025 ACM Web Conference.