Cataracts—a condition that causes clouding of the eye’s lens and deteriorating vision—will affect nearly everyone who lives long enough. Now Johns Hopkins scientists have pioneered a new color-changing hydrogel that could reduce complications from cataract surgery, one of the world’s most commonly performed procedures.

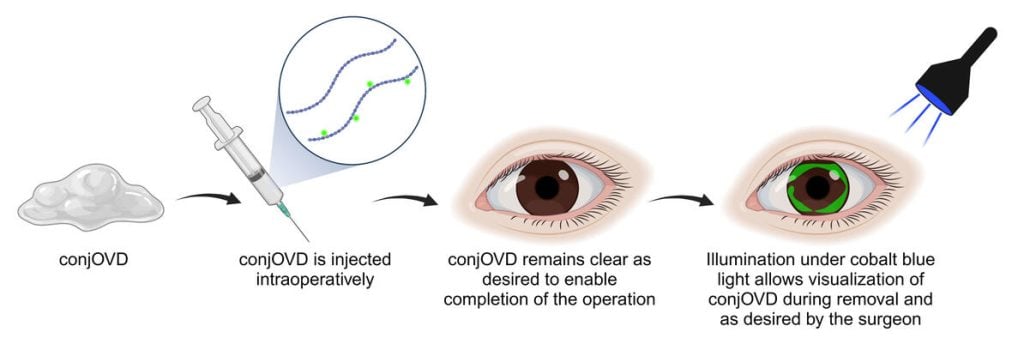

During cataract surgery, doctors remove the cloudy lens and replace it with an artificial one. The procedure requires injecting a clear hydrogel to keep the eye inflated and protect the cornea. However, incomplete removal of this gel can lead to increased eye pressure, pain, and even long-term vision loss.

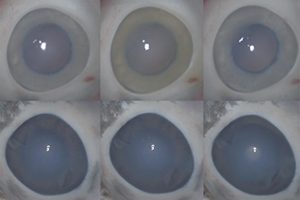

Erick Rocher, Engr ’24, and Allen Eghrari, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Wilmer Eye Institute, have created a clear gel that turns fluorescent green under blue light, allowing surgeons to verify complete removal following surgery. This innovation could enhance both the safety and efficiency of cataract surgery and other eye procedures, according to the researchers. Their results, “Fluorescein-conjugated hyaluronic acid enables visualization of retained ophthalmic viscosurgical device in anterior chamber” were featured on the cover of the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery in October. Rocher and Eghrari also filed a provisional patent application on the work.

“Because the gel has to be clear for the surgeon to operate, it’s very easy to leave some behind,” said Rocher, the paper’s first author and currently a research technician in the laboratory of Jordan Green, a professor of biomedical engineering. “Now, when surgeons finish up a case, they can rest assured that all the gel has been removed versus beforehand when they just had to do their best and hope they’d gotten it all.”

Rocher explained that scientists have previously tried to dye the gel—also called an ophthalmic viscosurgical device—with a staining agent, making it easier to see under blue light. But sometimes, the dye would leak out of the gel and spread into the eye, making it challenging for the surgeon to distinguish between the surgical gel and the dispersed dye.

In comparison, the new gel not only contains fluorescein and hyaluronic acid but also chemically bonds the fluorescent dye to the polymer that forms the gel. Under normal light during the operation, the gel appears clear, but once the operation is complete and the surgeon switches to blue light, the gel glows green, ensuring surgeons can see even the smallest traces of residual gel. The newest digital microscopes can even highlight the gel without requiring an additional blue light.

“In addition to more complete gel removal, a major plus is that we know each component is safe for the eye and already in clinical use,” said Eghrari. “Also, the chemical reaction that adds visibility to the gel doesn’t seem to significantly change its viscosity. That’s why we feel this is readily translatable: It feels very much like the gels that surgeons are familiar with.”

While the gel has shown promise in porcine models, researchers still need to evaluate its efficacy and safety in human trials. The team faces two key challenges ahead: scaling up gel production for clinical use and determining optimal dye concentrations. Rocher, who has been working with Eghrari since his freshman year, is optimistic about the gel’s potential.

“There’s a lot of possibilities with this gel. Sometimes the simplest innovations can be the most translatable,” he said.