Johns Hopkins engineers have uncovered new details about how granular materials such as sand and rock behave under extreme impacts—findings that could someday help protect the Earth from dangerous asteroids.

Using novel experimental techniques and advanced computer simulations, the team revealed that these materials can behave in unexpected ways when hit at high speeds, a finding that challenges traditional models. Their work appears in the Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids: “Quantifying 3D time-resolved kinematics and kinetics during rapid granular compaction, Part I: Quasistatic and dynamic deformation regimes.”

“Our study shows that different parts of a material, and even different grains of sand, can behave in very different ways during the same impact event,” said team leader Ryan Hurley, associate professor of mechanical engineering at the Whiting School of Engineering and a fellow at the Hopkins Extreme Materials Institute (HEMI). “What we found has the potential to inform applications ranging from asteroid deflection to industrial processes like tablet manufacturing.”

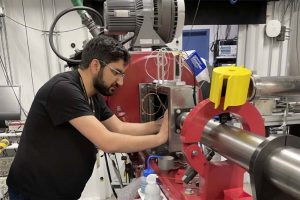

The team fired projectiles from a gas gun at velocities as high as 2 km/s into granular samples made of both aluminum and soda lime glass and observed the samples’ behaviors in the first few microseconds after impact. Though experiments like this are commonly done onsite at HEMI on Johns Hopkins’ Baltimore campus, this one took place at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) in Chicago because it required the use of special X-ray facilities for visualizing the impact.

“If you go to the beach, you can only see the sand on the surface, but an X-ray can see what’s going on underneath that,” said Sohanjit Ghosh, a PhD student of mechanical engineering and the paper’s lead author. “We combine X-ray images with numerical models that we’ve developed, and that makes the two-dimensional X-ray image into a three-dimensional process that gives us the full picture of what’s happening, both in time and space.”

Associate Professor Ryan Hurley

The researchers found that, in addition to other chemical reactions, the heat created by intense compression leads to the grains fracturing, melting, and re-solidifying.

“It is interesting to see how grains interact differently with each other at different impact velocities,” Ghosh said. “We found that when you go to higher and higher velocities, there’s so much thermal energy transmitted the grains actually melt and then reform.”

The team observed that different metallic materials exhibit distinct ways of dissipating energy during high-speed impacts. Materials such as aluminum absorb energy by the formation of defects and plasticity, while brittle materials like soda lime glass dissipate energy by fracturing and fragmenting.

The researchers say these findings could inform future missions similar to 2022’s DART mission, which struck an asteroid, altering its trajectory.

“All asteroids have this layer of sand, called regolith, on top of them, and when you shoot them, it’s the regolith that dissipates a lot of the impact energy,” Ghosh said. “We can infer from the combination of such modeling and experiments how different materials in different environments and impact conditions will behave.”

Ghosh said while the experiment’s planning lasted several months, the actual physical experience was over in a literal blink of an eye.

“The timescales of the experiments are very short—several hundred nanoseconds,” he said. “We prepare an entire experiment for a month and then it’s over in a few microseconds.”

Mohmad Thakur, an assistant research scientist at HEMI, was also a research team member.