People write with personal style and individual flourishes that set them apart from other writers. So does artificial intelligence, including top programs like Chat GPT, new Johns Hopkins University-led research finds.

A new tool can not only detect writing created by AI, it can predict which large language model created it, findings that could help identify school cheaters and the language programs favored by people spreading online disinformation.

“We’re the first to show that AI-generated text shares the same features as human writing, and that this can be used to reliably detect it and attribute it to specific language models,” said author Nicholas Andrews, a senior research scientist at Johns Hopkins’ Human Language Technology Center of Excellence.

“Few-Shot Detection of Machine-Generated Text using Style Representations,” which could reveal which programs are prone to abuse and lead to stronger controls and safeguards, was recently presented at a top AI conference, the International Conference on Learning Representations.

The advent of large language models like ChatGPT have made it easy for anyone to generate fake writing. Much of it is benign, but schools are wrestling with plagiarism, and bad actors are spreading spam, phishing, and misinformation.

Following the 2016 election and concerns surrounding foreign influence campaigns on social media, Andrews became interested in developing technologies to help combat misinformation online.

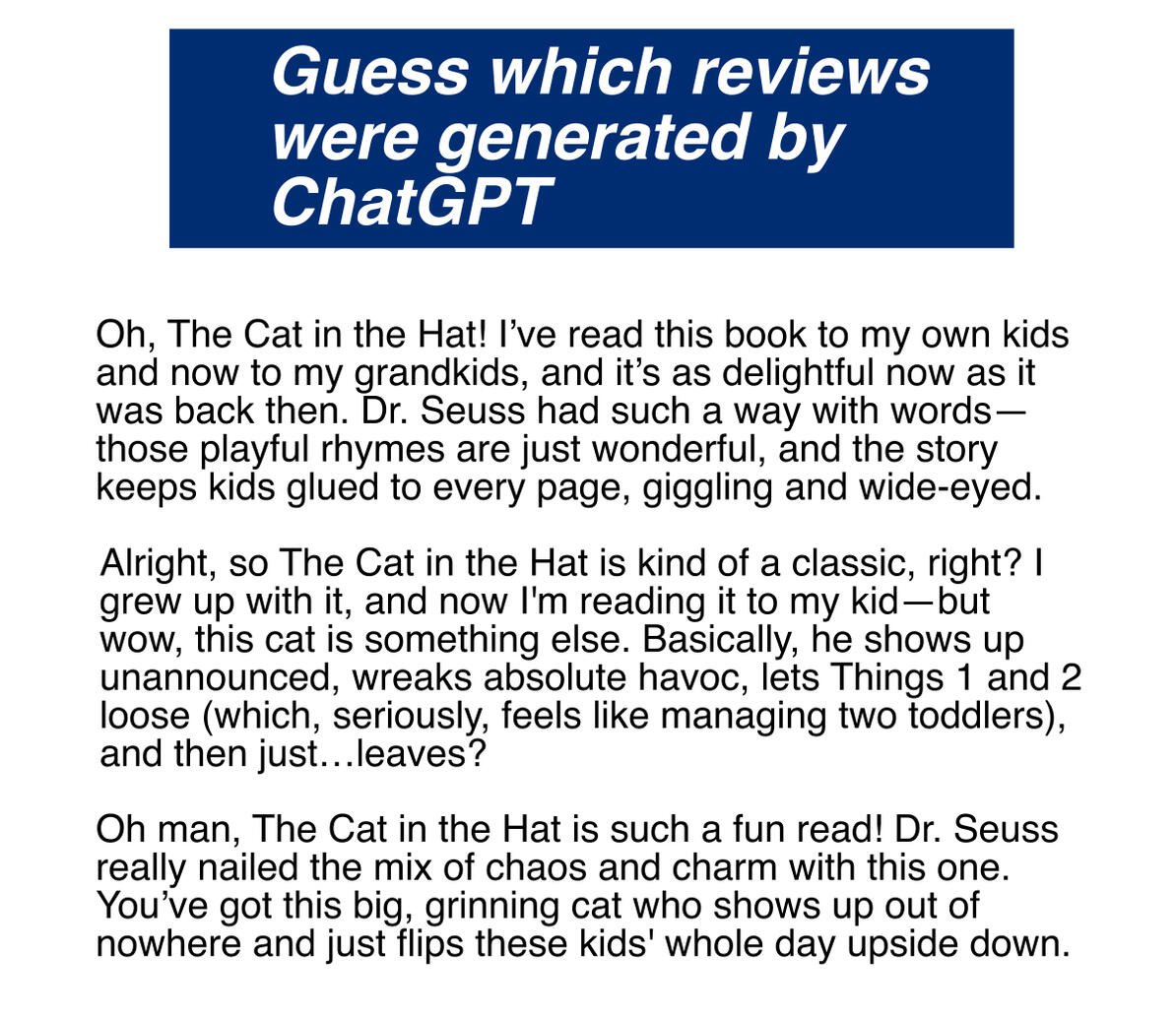

A popular machine-text detector GPTZero misidentifies the first review as being written by a human. All three reviews are machine generated using GPT-4.

“I said let’s try to build a fingerprint of someone online and see if those fingerprints correspond to any of the disinformation we’re seeing,” Andrews said. “Now we have this hammer we spent years building, and we can apply it to detect what’s fake and what’s not online. Not only that, we can figure out if it was ChatGPT or Gemini or LLaMA, as they each have linguistic fingerprints that separate them from not only human authors but other machine authors, as well.

“The big surprise was we built the system with no intention to apply it to machine writing and the model was trained before ChatGPT existed. But the very features that helped distinguish human writers from each other were very successful at detecting machine writing’s fingerprints.”

The team was surprised to learn that each AI writing program has a distinct style. They’d assumed all machine writing would share the same generic linguistic fingerprint.

Their detection tool, trained on anonymous writing samples from Reddit, works in any language. It is available for anyone to freely use and download. It has already been downloaded about 10,000 times.

The team is not the first to create an AI writing detection system. But its method appears to be the most accurate and nimble, able to quickly respond to the ever-changing AI landscape.

“Law enforcement originated this concept, parsing ransom notes and other writing by suspected criminals and trying to match it to individuals,” Andrews said. “We basically scaled that up. We took away the human, manual process of defining these written features, threw lots of data at the problem and had neural network decide what features are important. We didn’t say look at exclamation marks or look at passive or active voice. The system figured it out and that’s how we were able to do much better than people have.”

When the team presented the work at the International Conference on Learning Representations, lead author Rafael Rivera Soto, a Johns Hopkins first-year PhD student advised by Andrews, created a thought-provoking demo. He ran all the peer reviews from the conference through the detector. It flagged about 10% of the reviews as likely machine generated—and probably ChatGPT.

Authors include Johns Hopkins doctoral student Aleem Khan; Kailin Koch and Barry Chen of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; and Marcus Bishop of the U.S. Department of Defense.