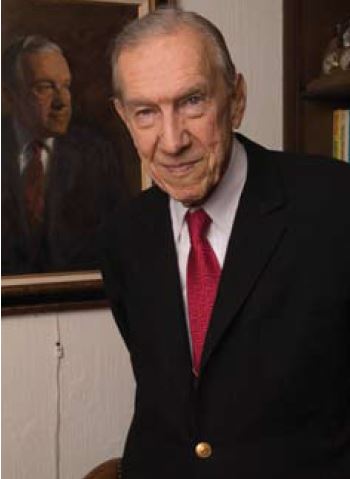

On a warm spring morning this past April, John Rettaliata ’32, PhD ’36, reclined in a chair in his suburban Chicago home and recalled his days at Johns Hopkins Engineering—and the high points of his illustrious 70-year career. Over the decades, Rettaliata has witnessed the ends of wars, helped usher in the beginnings of eras, and has, time and again, made significant and long-lasting contributions to the advancement of technology and society. Among his many accomplishments are the 21 years he served as president of the Illinois Institute of Technology, a position on President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s first aeronautics committee, and the distinction of being one of the first humans to fly in a jet aircraft.

As a teenager, Rettaliata attended Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, which prepared him to enter Hopkins Engineering as a sophomore in 1929. He studied under the advisement of Professor Alexander Graham Christie. “He only had about three or four pupils,” Rettaliata recalls. “We’d sit around his table and that’s how we’d conduct our courses, studying steam and gas turbines.” Those table- side conversations led to enhancements in the ways the turbine could extract thermal energy from pressurized steam, converting the energy into mechanical labor, he recalls.

When Rettaliata left Hopkins in 1936 with his freshly minted PhD, Christie helped him secure a job in Milwaukee at Allis-Chalmers, a leading manufacturing company in the Midwest. He worked in the Steam Turbine Department for eight years building turbines for military destroyers, and his diligence earned him a position on the U.S. National Advisory Council’s subcommittee on aeronautics gas turbines. During World War II, he continued his work with the United States Government; he joined a group of government-contracted aerospace experts on a tour of British aeronautical research facilities—work that ultimately led to America’s first jet aircraft and dominance in aeronautical research. The work also had a personal pay-off: Rettaliata became one of the first people ever to fly in a jet.

As World War II came to a close, the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Ships dispatched him to Europe to, as he puts it, “see what the Germans were doing.” For weeks he was delayed in Paris, waiting for the war to end, and when it did, he accompanied the U.S. government into Germany. Rettaliata was one of the first to inspect the factories in which the opposition had built their submarines.

What he found was astonishing.

At the time, submarines were powered by diesel engines when they sat on the surface of the ocean but had to resort to battery power when they went below the surface, a switch that decreased their power and limited their speed. However, Rettaliata says, the German submarines could travel at up to 20 knots, more than twice the speed of their American counterparts that ran at 9 knots. When Rettaliata, by then a recognized expert in steam and gas turbines and engines, inspected the now-defunct military’s U-boat factories, he discovered that the Germans weren’t zooming along at 20 knots on battery power; they had devised a way for their motors to run within the ocean’s depths.

As he made his way through the factories, Rettaliata learned the German engineers’ secret. “We called it a Hydrogen Peroxide Machine, because that’s what they ran it off of,” he says. To store the liquid, they filled the space between the inner and outer hulls with it. They could then disassociate it, remove the oxygen, and use it to run their engines underwater.

Returning to the U.S., Rettaliata joined the faculty of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in 1945 and relocated to Chicago, where he still lives today. At IIT, he rose quickly to become its dean in 1948, vice president of academic affairs in 1950, and president in 1952 at just 40 years old.

As president, he led the school for more than 20 years, overseeing an explosion of growth for the school. “If you don’t have good faculty, you’ll go out of business,” he says now. Therefore, he set out to make IIT a place where people would love to teach. He initiated ambitious fundraising efforts that secured a $20 million annual budget, oversaw the con- struction of a new downtown campus center (along with architect Mies van der Rohe), and guided IIT to national prominence.

Seven years into his tenure as president, Rettaliata was asked to join President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s National Aeronautics and Space Committee. “We’d meet twice a month in his Cabinet room. We were drawing plans for space exploration,” Rettaliata says. That committee eventually evolved into NASA. And, 40 years ago, his brother gave me a very illustrious award,” he says, referring to one of the university’s first Distinguished Alumnus Awards, bestowed upon him in 1963 by university president Milton S. Eisenhower.

Today that award hangs in Rettaliata’s study, on the second floor of his office in his Chicago home. The walls of his office are covered with other illustrious awards— from mayoral proclamations to military commenda- tions to the Chicago Gold Medal of Merit and a fellowship from the American Society of

Mechanical Engineers. He also holds six honorary doctorates, from De Paul University, Chicago-Kent College of Law, the Michigan College of Mining and Technology, Rose Polytechnic Institute, Valparaiso University, and Loyola University.

Rettaliata retired from IIT in 1973 (“Twenty-one years as president was a long time,” he says chuckling), then became the chairman of Chicago’s Banco de Roma, which he led for six years. From there he continued to sit on at least 15 various boards, ranging from Johnson Wax and Western Electric to Sante Fe Southern Pacific and the Interna- tional Harvester Company.

Now 96, this kind and unassuming man is happy once and for all to be fully retired. “Oh, I try to stay out of trouble. I’m off all the boards, but I keep busy,” he says. Along with his wife, Caryl, Rettaliata now spends half his year at home and the other half on their yacht, which stays docked at Chicago’s Burnham Harbor. “I’m mainly attracted to the yacht because of the engine. There’s always something to do in the engine room of a boat,” he says with a contented smile. “I could live in an engine room.”