Whether they share their vision on a flash drive or scrawled on a paper napkin, engineering faculty and students know they can count on experts in the Whiting School’s Machine Shop to bring ideas to life.

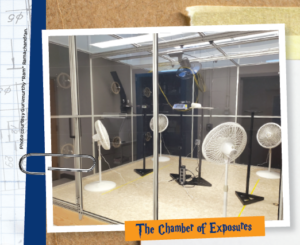

Professor Gurumurthy “Ram” Ramachandran and his team in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering faced some daunting challenges when they set out to build an environmental chamber to simulate workplace settings.

Their goal was to replicate industrial tasks that generate chemicals, fumes, and dusts to measure their airborne concentrations. To do that, the researchers would need to be able to control the rate of air flow in the chamber over a wide range and easily clean its surfaces between uses. And the entire facility would have to be constructed as an airtight space within the confines of their existing lab at JHU’s Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Their goal was to replicate industrial tasks that generate chemicals, fumes, and dusts to measure their airborne concentrations. To do that, the researchers would need to be able to control the rate of air flow in the chamber over a wide range and easily clean its surfaces between uses. And the entire facility would have to be constructed as an airtight space within the confines of their existing lab at JHU’s Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Needing guidance and expertise, Ramachandran and his team did what countless other engineering faculty members and students at Johns Hopkins do: They visited the Whiting School’s Machine Shop. Located in the basement of the Homewood campus’ Wyman Park Building, the shop is a beehive of activity where saws buzz, drills whir, and sparks fly. It’s here that a team of nine machinists, engineers, instrument designers, and others help university affiliates with consultation, design and manufacturing, and services and repair.

For Ramachandran’s project, Machine Shop engineers suggested materials for the walls that would be easy to clean and would be inert to the various chemicals and conditions being tested, and working with the building’s managers, they were able to tie into the existing ventilation and drainage systems.

“They were very thoughtful about every aspect. In fact, one of my favorite details was that one of my students suggested calling the chamber ‘The Chamber of Exposures,’ after Harry Potter’s Chamber of Secrets.” The shop’s engineers clearly enjoyed the comparison and surprised Ramachandran and his students by creating a sign for the external wall, written in a Harry Potter-style font.

A Decade of Ideas

In 2008, when Rich Middlestadt joined Johns Hopkins Engineering as a machinist in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, he quickly became aware of student and faculty members’ ever-growing need for assistance with conceptualizing, designing, and creating innovations that would enable them to address complex engineering problems, as well as inefficiencies that he observed that made it challenging to provide such support in an effective and efficient manner.

“I realized there was a disconnect between the departments. Each had their own resources and facilities to handle their own needs,” he says.

From that need, WSE Manufacturing was born, with Middlestadt as its founding director. Today, the facility encompasses a machine shop as well as a student self-service facility and a makerspace (see below for more information), all of which provide the Engineering School and the JHU community with consultation and manufacturing services and access to equipment and resources.

Daren Ayres, senior instrument designer who has been with the Machine Shop since it opened in 2013, explains, “You never know what sort of request will walk through the door.” He has worked on projects ranging from repairs to the Gilman clock tower’s hands to lifesaving medical devices.

“Right now, I’m milling these little chambers that grow human tissue.” He holds up a clear Lucite rectangle about one inch thick and the size of a credit card. He is drilling tiny holes into its sides where he’ll insert minuscule rubber O-rings—about the size of the “o” on this page—to form a vacuum-sealed chamber in its center.

The devices, called bioreactors, are being made for Danielle Yarbrough, a third-year PhD student in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, whose team is investigating how different tissue engineering models are affected by space flight. In 2021, the Machine Shop created the first bioreactor, designed by Chelsey Dunham, a former postdoctoral fellow in the lab, and they have made eight more since.

The bioreactors enable Yarbrough to grow models of human blood vessels, using a process that involves inserting two needles into the hollow port at the device’s center into which she then inserts a tube of tissue tied to a polymer scaffold.

“We’re studying how cells respond to different disease conditions with the goal of modeling various cardiovascular diseases,” explains Yarbrough. “Currently, we either look at cells in a dish or use a mouse model, so this is an in-between way, or an in-vitro culture system, to study effects on actual human cells.”

“We’re studying how cells respond to different disease conditions with the goal of modeling various cardiovascular diseases,” explains Yarbrough. “Currently, we either look at cells in a dish or use a mouse model, so this is an in-between way, or an in-vitro culture system, to study effects on actual human cells.”

The ultimate goal of the project, which is funded by a branch of NASA’s Human Research Program, the Translational Research Institute for Space Health, is determining a way to protect astronauts from radiation and understand the effects of deep space travel on the cardiovascular system.

“You never know what sort of request will walk through the door.”

– Daren Ayres, senior instrument designer

Boundless Ingenuity

“The geniuses on campus have befriended the machinists and bring us ideas—whether on a flash drive or a paper napkin,” says Cindy Larichiuta, the Machine Shop’s

program administrator. “We are like a chameleon who is constantly changing its colors to adapt to anything they need. We touch everything under the university umbrella—from the newest breakthrough for surgery to a refrigeration unit that needs to be moved across campus— because we have the expertise and resources to do both.”

Mark Cooper, a senior instrument designer, also appreciates the variety of projects. “One of my favorite things about working here is that you never know what ideas these engineers are going to come up with. And they often have no idea how to make what they have conceptualized. That’s where we come in,” Cooper says.

One of Cooper’s first projects was made at the request of a researcher studying water droplet deviations in a controllable-strength electromagnetic field. The researcher needed a voltage field plate system that would enable him to understand the effects of strength of electromagnetic field on varying droplets per second. Cooper’s solution was to build a stand with two copper plates that could swing out at increasing increments of rotation to adjust the distance between them while 5,000 volts of current ran through them and water droplets dripped through the field.

“The challenge in this case was connecting wires to copper plates that would conduct electricity—with water—and not get electrocuted or set anything on fire,” Cooper says.

“One of my favorite things about working here is that you never know what ideas these engineers are going to come up with. And they often have no idea how to make what they have conceptualized. That’s where we come in.”

– Mark Cooper, senior instrument designer

Stipe Iveljic, a senior instrument designer, is known by his peers as the master of tiny things. For instance, he machined a small bone-mounted marker that can be screwed into place and is used to measure the precise 3D location and angle of a spinal vertebra during scoliosis surgery.

The device was a key component of a technology developed by Spine Align, a local startup from the Whiting School’s Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design, led by master’s students Amir Soltanianzadeh MS ’18 (CEO and co-founder) and David Gullotti MS ’17, MD ’19 (SOM) (CTO and co-founder, now interventional radiology resident), and Nick Theodore (co-founder and director of the Neurosurgical Spine Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital).

“Having the right equipment here in our shop makes this challenging job a little bit easier for me,” says Stipe. “I truly enjoy helping students and faculty with research that might lead to developing new medical devices or procedures.”

Room to Grow

One result of WSE Manufacturing’s success, ironically, is that the team has outgrown its original space in the Wyman Park Building. Due to space restrictions and ventilation requirements, they have some facilities in other buildings. A pending renovation to the Wyman Park Building may enable them to double—or even triple—in size and consolidate operations with the Machine Shop at its center, once again giving form to Middlestadt’s vision.

Regardless of where the shop is located, it will continue to serve its purpose: offering engineered solutions for people across the university.

///SELF-GUIDED INNOVATORS///

In the self-service machine shop, open 24/7, students have access to a full range of equipment they need to bring their projects to fruition.

One group that relies on this self-service shop is Blue Jay Racing, an undergraduate team that takes part in competitions sponsored by Baja SAE, an international organization that challenges students to build from scratch a vehicle that can withstand the severe punishments of rough terrain, mud, and water at sponsored events across the country.

Lance Phillips, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student, is this year’s team lead. “Being in Baja has given me hands-on, real-world engineering experience that I wouldn’t have necessarily gotten in the classroom. I have learned to weld and to use subtracting manufacturing machines, like mills and lathes,” he says. “My first internship was the direct result of participation in this club.”

There are about 25 people on the team this year. They planned their design last summer, have been building their vehicle throughout the school year, and this summer will compete against approximately 200 teams representing university engineering programs from 14 nations.

///WHERE IDEAS SHINE///

— Koye Berry

The Makerspace, a manufacturing and design space managed by the Whiting School, is the go-to hub for innovative projects of all kinds. Serving all Johns Hopkins university affiliates, it is outfitted with 3D printers, vinyl and laser cutters, an electrical station, and more.

The Makerspace, a manufacturing and design space managed by the Whiting School, is the go-to hub for innovative projects of all kinds. Serving all Johns Hopkins university affiliates, it is outfitted with 3D printers, vinyl and laser cutters, an electrical station, and more.

This year, the facility was used for a semester-long team project to create Persephone: Four Seasons, an interactive light and sound organ created for the annual lighting of the quads ceremony in December. The facility’s first-ever partnership with Johns Hopkins University’s Digital Media Center, the team was led by Makerspace manager Luke Ikard, and Jason Charney, multimedia specialist for the Digital Media Center.

The interactive synthesizer resembled a pipe organ, which produces columns of led light that correspond to each key. Inspired by the myth of Persephone and the changing of the seasons, the LED colors and musical modes evolve as the instrument is played.

“Jason led the technology aspect of the project,” Ikard says. “We worked with the students to develop the physical structure and how we wanted users to interact with it. That’s where the Makerspace shines; we have larger prototype manufacturing equipment that can produce on this scale. We used our woodshop and our CNC router to import 2D designs and cut them perfectly out of plywood. Being able to design that kind of custom object is what we excel at.”

The light organ was showcased at three campus events this year: the Lighting of the Quads, a night at the ice rink, and the Alumni Weekend arts showcase.