Surgery on the retina, the thin, transparent layer of light-sensitive tissue that lines the inside of the back of the eye, is excruciatingly delicate. Retinal scar tissue caused by such common diseases as macular pucker, diabetic retinopathy, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy can ruin someone’s vision, and yet to remove it, a surgeon has almost no room for error.

The retina is about 250 microns thick and very fragile. Some scar tissue is no more than 3 microns thick and transparent to boot. And when even a good eye surgeon can have 40 microns of hand tremor that must be compensated for, removing the scar tissue is very difficult and not always successful. Surgeons sometimes have had to accept small areas of injury in order to recover larger or more vision-critical areas of the retina.

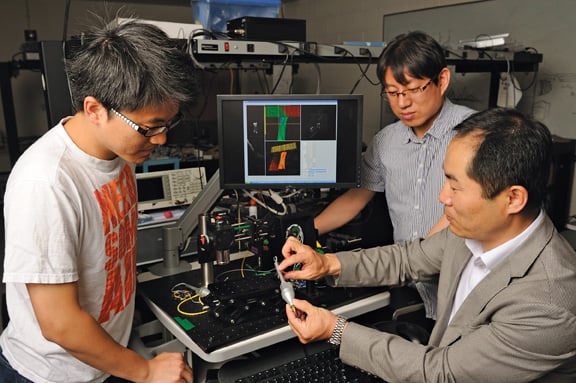

But not for long, thanks to a “smart” surgical tool developed by Jin Kang, chair of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Whiting School. Kang, an expert in fiber optics, worked in collaboration with Hopkins’ Engineering Research Center for Computer-Integrated Surgical Systems and Technology to create a tool system that can help surgeons perform all kinds of microsurgery-not just eye surgery-beyond the limits of human dexterity.

A laser probe, made of a tiny fiber-optic cable, emits light that bounces off the surrounding tissue to image and measure the distance between the fiber tip and the tissue boundaries. “It’s like a sonogram but on a smaller scale-in nanometers, microns, or millimeters,” says Kang. “And we can implement it onto a variety of freehand surgical tool tips such as a knife or needle or forceps.”

This tip is then connected to a motor that controls the axial movement of the tool tip. The system senses the movement of the tool tip relative to the surgical surface and automatically adjusts the tool tip position to allow surgeons to perform procedures safely and accurately. Kang likens the tool system to automatic stability and traction control systems in modern cars that make the driving safe in slippery conditions. This system has been shown to be highly effective in removing the surgeon’s hand tremor.

“Say a surgeon wants to do gene therapy and insert genes into a layer of retinal tissue only 50 microns from the surface,” says Kang. “This tool automatically senses how far the tip is from the surface and tells the tool tip to go exactly 50 millimeters and the surgeon can inject the genes without even really having to think about it.” Moreover, the tool can be integrated as a part of a robot to control the fine tool tip movements.

Kang and his colleagues have been developing this fiber optics sensing/imaging technology since 2004. For the past three years, Kang has worked closely with Peter Gehlbach, associate professor of ophthalmology in the retina division of Johns Hopkins’ Wilmer Eye Institute, to develop the tool.

Says Gehlbach, “This human-tool interface allows us to explore a realm in surgery never before accessible: We’ll be able to do things we’ve never done before.