“It was a big surprise to find how willing people from many different disciplines were to engage with the infrastructure problem intellectually.” That enthusiasm, he suspects, is part of a larger awareness developing among non-engineers as well. The American public, he believes, recognizes the need to get serious about the infrastructure problem. “I think there is a window of time during which people are open to it. Five years ago if you said the word ‘infrastructure,’ by the time you got to the second syllable people were asleep.”

“It was a big surprise to find how willing people from many different disciplines were to engage with the infrastructure problem intellectually.” That enthusiasm, he suspects, is part of a larger awareness developing among non-engineers as well. The American public, he believes, recognizes the need to get serious about the infrastructure problem. “I think there is a window of time during which people are open to it. Five years ago if you said the word ‘infrastructure,’ by the time you got to the second syllable people were asleep.”

The resulting $17 million, five-year grant proposal is now under second-round review at the National Science Foundation. If approved, the Mid-Atlantic Center for Infrastructure Robustness and Renewal (or MAC-IR2 as the grant proposal playfully suggests) will be based in the Whiting School at Johns Hopkins but will draw from across the university, as well as from Howard University, the University of Maryland, the Maryland Institute College of Art, Virginia Tech, the University of Sydney, Australia, and TU-Dresden, Germany.

Clearly, the needs for an integrated approach are manifold. Tom Stosur has been with the City of Baltimore for 22 years and since February 2009 has served as director of the Department of Planning, the office charged with developing the city’s overall capital budget based on a six-year projection of what the city needs to spend on infrastructure. Ask him for his “dream list” of what he’d like to do and he quickly rattles off the city’s needs: $2 billion for the schools, another $2 billion for water and sewer, perhaps $3 billion for cleaning up our waterways leading to the Bay, and a whopping $10 billion to $15 billion on transit— and that doesn’t include funds to finance necessary roadway, bridge, pedestrian, and bicycle networks. “A billion dollars doesn’t go very far today,” he says sadly.

“Our greatest need is to integrate systems so that while you’re upgrading water and sewer lines you’re also fixing parks and planting trees—in other words, you want to maximize opportunities.” Tom Stosur, director of Baltimore City’s Department of Planning

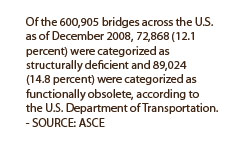

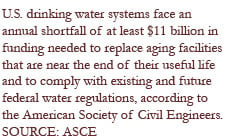

Chief among the Planning Department’s responsibilities is keeping track of the condition and needs of the “traditional” infrastructure, consisting of the water and sewer system, the storm water system, the roads and transportation infrastructure, street lighting and stoplights, and the underground conduits that include fiber optics, gas, phone, and electric networks. Then there is the “green” infrastructure of the parks, city trees, and watershed; and the “systems” infrastructure of schools, recreation centers, trash collection centers, and landfill—all critical components of the quality of life in a major metropolitan area, and almost all owned, operated, and maintained by the city. “That’s our bread and butter,” he says, “to keep them functioning.” It is a task for which needs constantly outstrip resources. “The water and sewer system goes back more than 100 years, and in some cases there are not complete records of what’s down there,” Stosur says. “There are major investments that need to be made in the water and sewer systems, including the current consent decree with the EPA that requires us to invest $1.4 billion over eight to 10 years in upgrading the sewer system. There is so little funding compared to the need that the urgent stuff is generally all that gets done.”

Like Erica Schoenberger, Stosur believes that really smart engineering is the key to a better infrastructure future. “There is no magic bullet,” he says. “We have to keep renewing, and we have to learn how to spend money more smartly. Engineers are the key. Our greatest need is to integrate systems so that while you’re upgrading water and sewer lines you’re also fixing parks and planting trees—in other words, you want to maximize opportunities. It’s about learning to see the connections that can be made.”

Like Erica Schoenberger, Stosur believes that really smart engineering is the key to a better infrastructure future. “There is no magic bullet,” he says. “We have to keep renewing, and we have to learn how to spend money more smartly. Engineers are the key. Our greatest need is to integrate systems so that while you’re upgrading water and sewer lines you’re also fixing parks and planting trees—in other words, you want to maximize opportunities. It’s about learning to see the connections that can be made.”

But making those connections may be one of the biggest challenges facing any program of infrastructure renewal. “We’re at the moment of understanding that we’ve created systems that are much more complex and highly interrelated than we understood,” says Ben Schafer. “Every part is interconnected, so we are trying to figure out systems-level modeling as a way of thinking things through.” The trick is devising a useful model of decision making that not only makes the connections between interlocking opportunities but also finds a rational way of resolving conflicting and sometimes contradictory demands in an environment of limited resources. “You have to be able to answer the question, Is it worthwhile?” says Whiting School civil engineering professor Takeru Igusa. “The traditional cost/benefit analysis doesn’t work because it is too narrowly focused on specific inputs and outcomes. What we need to be able to measure is how these projects touch on the larger aspects of society as well.”