Their low-cost cushion with sensors to prompt better posture proves they’re no slouches when it comes to ingenuity.

“I’m one of those people whose mother was always telling them to sit up straight,” laughs Yen Shi Gillian Hoe ’04. That is exactly what judges did at the international Start-Up @ Singapore business competition (www.startup.org.sg/) last May when she and fellow inventors Bhuvan Srinivasan ’04 and Elbert Hu ’04 unveiled their plan. Their project, the Interactive Posture Analyzing Cushion (IPAC), is an innovative— and elegantly simple—device for improving and maintaining good posture.

As Biomedical Engineering seniors at the Whiting School of Engineering, the three first teamed up during a January 2004 Intersession course called “Honors Instrumentation.” They had three weeks to design, research, and build a prototype of a functional medical device.

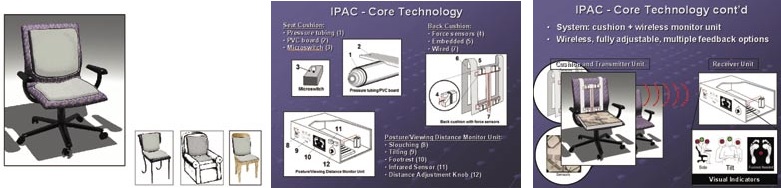

Using easy-to-buy, energy-efficient parts, the IPAC was, according to Hu, designed to fit a niche between “expensive ergonomic chairs and non-interactive software alarm systems” currently available for improving posture. According to their IPAC business presentation, 80 percent of Americans experience back pain, and ergonomic hazards account for 35 percent of the Department of Defense’s $600 million bill for civilian workers’ compensation.

Says Hoe, “Knowing what we did about sensors, we figured we could create a device that doesn’t force you into a posture, as expensive chairs do. We were looking for a less expensive and more flexible solution.” The resulting device features a seat and back cushion with built-in sensors and microcircuitry that wirelessly communicates with a tabletop box with LED displays. The displays alert users when their posture is poor and when they need to get up and stretch.

After the IPAC won “best in class” for technical excellence, the team was encouraged to develop a business plan for transforming its good idea into a great product. Their plan took third place in the annual Business Plan Competition sponsored by the Center for Leadership Education, and at the Greater Baltimore Technology Council Mosh Pit business plan competition. With support from Murray B. Sachs, Massey Professor and director of the Whitaker Biomedical Engineering Institute at Hopkins, the team decided to search for more competitions to test its idea.

“We looked on the web and found tons” of international venues, explains Srinivasan. “The one that was closest to the time we were working on the device was Start-Up @ Singapore. The top prize was $30,000, and that was very interesting,” he says. The competition attracts college teams, start-up companies, and others.

Their team applied and made the semifinals at the international competition. That’s when Biomedical Engineering really backed them. According to Hu, “There is no way we could have gone with- out the department. They paid for our airplane tickets, and they were all so supportive.”

Preparing for a competition on campus or in town is one thing. “When it came to going all the way to Singapore, presenting in front of judges we had never met, it was like being thrown out of our cocoon,” says Srinivasan. “If it had not been so extremely exciting, I would have broken down from nervousness.” All of them had been in Singapore before. Srinivasan, a native of India, attended high school in Singapore, where his parents still live. Hoe was born there but grew up in the Philippines. Hu was born in America but lived for many years in Taiwan, where his family is from. He had visited Singapore “once or twice for track meets during high school,” he says.

During their whirlwind trip halfway across the globe, they had little time to be nervous. According to Srinivasan, whose mom and dad provided them with lodgings in Singapore, “To this day, my parents claim they never saw me in May…and that I still owe them a visit.”

“Right after finals,” Hu relates, “we hopped on the plane to Singapore.” They missed Senior Week’s activities, but he wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Every minute leading up to their presentation, they continued to work on getting it together and refining their ideas. “There was not much time for sightseeing,” Hu explains. “We had heard the judges were very interested in biotechnology because Singapore is seeking to become a hub of biotech for Southeast Asia. We were working on ways to push those aspects of the plan.”

As they hurried to make final changes in the last hours before their presentation for the panel of judges, they experienced every high-tech visionary’s worst nightmare.

“We were finishing up at sunrise,” Hu recalls. “We kept thinking of more ways to sell the product and target additional customers. We developed multiple versions of the product for corporate customers and individual customers. The plan was getting more complicated and branching out.” Srinivasan was crunching numbers as Hoe created new PowerPoint® slides to explain the charts and graphs. Then their business modeling software locked up. There was nothing to do but reboot, which dumped all of the valuable statistics, charts, and graphs.

“What had taken us days to create, we had to put back together in less than one hour.” Elbert Hu ’04

“Bhuvan maintained his calm,” Hu says. “What had taken us days to create, we had to put back together in less than one hour.” The final half-hour before their appearance, they were at Srinivasan’s father’s office, plugging in the last figures, adding new information, and frantically finishing slides. “And then we ran to the competition with the presentation completely recreated,” he recalls.

In the end, their IPAC idea did not win the top prize. Hu spec- ulates that this might have been because “Asian audiences don’t really have the regulatory climate that we have here, so apprecia- tion of the importance of the IPAC” may not have been as great as the team anticipated.

But the experience was not wasted on the participants. Hoe says, “We all had a great time and truly appreciate the University’s sponsoring us. It feels like they really want to support new ideas, that they encourage students to extend themselves just as far as they will go.”

All three demonstrated their ingenuity with other projects as well. Hu and Hoe (now graduate students in the Whiting School) as undergraduates were part of a Whiting School student team that invented a medical device to precisely measure the conductivity of a pregnant woman’s cervical tissue, thus preventing premature delivery. Hoe also was on the student design team that invented an unobtrusive wireless device to measure the amount of force a physician or midwife uses in delivering a baby. Now being tested at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, the device could help identify the safest method for delivery in complicated births. And Srinivasan was part of student research team that mapped the interaction of molecules within a cardiac cell; understanding these microscopic movements could lead to predictions of what’s happening in the heart. The students presented their findings at two prestigious computational biology conferences. Srinivasan was delighted to find how much support Hopkins gives to undergraduates who undertake research.