Sudden bursts of energy are found on earth at the smallest and largest of scales, but how similar are they dynamically? A team of Johns Hopkins engineers has found that these energy bursts, from a micro-tear to an earthquake, actually follow the same statistical principles.

Their findings, “Toward a universal framework for avalanche dynamics: From crystal slip to fault slip,” published in Acta Materialia, could enable a better understanding of the fundamental mechanisms behind deformation in metals. The team, led by Jaafar El-Awady, a professor of mechanical engineering, believes their research can improve how material failure is modeled and predicted in engineering applications.

“Understanding these universal patterns could help engineers design more resilient structures and components and improve predictions of when and how materials will fracture,” El-Awady said. “Ultimately, the goal is to use these insights to design stronger, more reliable materials and to refine predictive models for systems that experience sudden, burst-like energy releases, whether deep in the Earth or within engineered structures.”

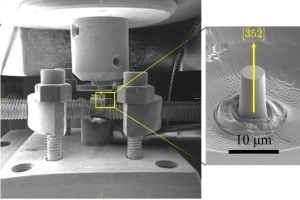

The team compressed nickel micropillars—each about one-tenth the width of a human hair—while using sensitive acoustic equipment to monitor the sounds they produced. Acoustic emissions system offers higher acquisition rates than mechanical testing alone, allowing the researchers to probe the dynamics of deformation a much faster rate than just visual observation. The compression triggered what’s known as a dislocation avalanche, essentially a tiny earthquake. The engineers found that the same statistical laws governing large earthquakes also apply to the micro-scale events, despite their differences in size, by more than 10 orders of magnitude.

“This remarkable similarity revealed that the phenomena share universal physical principles, despite occurring at vastly different scales, from nanometers in metal crystals to kilometers in the Earth’s crust,” said Mostafa Omar, postdoctoral fellow and lead author of the team’s paper. “We observed foreshocks, mainshocks, and aftershocks every instance.”

Metal deformation looks to the naked eye like a sudden occurrence, but at a microscopic level tiny defects shake and alter the metallic fabric in a cascading fashion in a rise-and-decay trend. The same is true of a large-scale mudslide caused by seismic activity. El-Awady explained that the same mathematical principles that dictate how energy is released are being followed in both cases.

“This research reveals universal principles governing how complex systems fail and release energy,” he said. “We set out to bridge the gap between geophysics and materials science, and this work shows that they share a distinct mathematical framework.”

The researchers now plan to investigate why some avalanche sequences deviate from classical earthquake laws over longer timescales and to test more materials to determine whether similar patterns of frequencies and energy distributions appear in other materials.