“As soon as I looked at the microscope images, I noticed that there were these little nanospheres and they were iron-rich, and they have lots of different elements in them besides iron—silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium —and they all varied.”

“As soon as I looked at the microscope images, I noticed that there were these little nanospheres and they were iron-rich, and they have lots of different elements in them besides iron—silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium —and they all varied.”

– Ken Livi

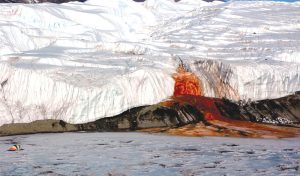

During the Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica in 1911, British Geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor discovered a mysterious waterfall of what appeared to be blood discharging from beneath the glacier that now bears his name. The water emerges clear but quickly turns crimson—a phenomenon Taylor dubbed “Blood Falls.”

Using powerful transmission electron microscopes, Ken Livi, an associate research scientist in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and director of operations for the Whiting School of Engineering’s Materials Characterization and Processing facility, examined samples of Blood Falls water and found an abundance of iron-rich nanospheres that oxidize, turning the water seemingly gory and solving a century-old mystery.

Previously, researchers believed minerals caused the red water, but unlike minerals, nanospheres are not crystalline, so they went undetected.

“As soon as I looked at the microscope images, I noticed that there were these little nanospheres and they were iron-rich, and they have lots of different elements in them besides iron—silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium—and they all varied,” Livi says.

Livi worked on the project with a team that included experts at other institutions, including Jill A. Mikucki, a University of Tennessee microbiologist who has been investigating the Taylor Glacier and Blood Falls for years. Their results appeared in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

A prolific Antarctic researcher, Mikucki was part of the team that first identified living organisms in the lake beneath the Taylor Glacier. That team mapped the water’s source: an ancient, briny subglacial reservoir containing myriad minerals gathered by the ice in its crawl across the rocks below. The reason for the water’s startling gory appearance, though, remained unclear. So Mikucki and astronomer Darby Dyar from Mount Holyoke College sent the samples to Livi at the Materials Characterization and Processing facility.

Livi, a planetary materials expert, says that the ancient, iron- and salt-rich waters under the Taylor Glacier host bacteria strains that may be millions of years old and could inform the search for life on other seemingly inhospitable planets, including Mars.

“There are microorganisms that have been existing for potentially millions of years underneath the saline waters of the Antarctic glacier,” he says. “These are ancient waters.”