“These findings could inspire new treatment for mucus-related illnesses, including chronic lung diseases and mucinous cancer, the deadliest subtype for lung and ovarian cancer.”

— Yun Chen

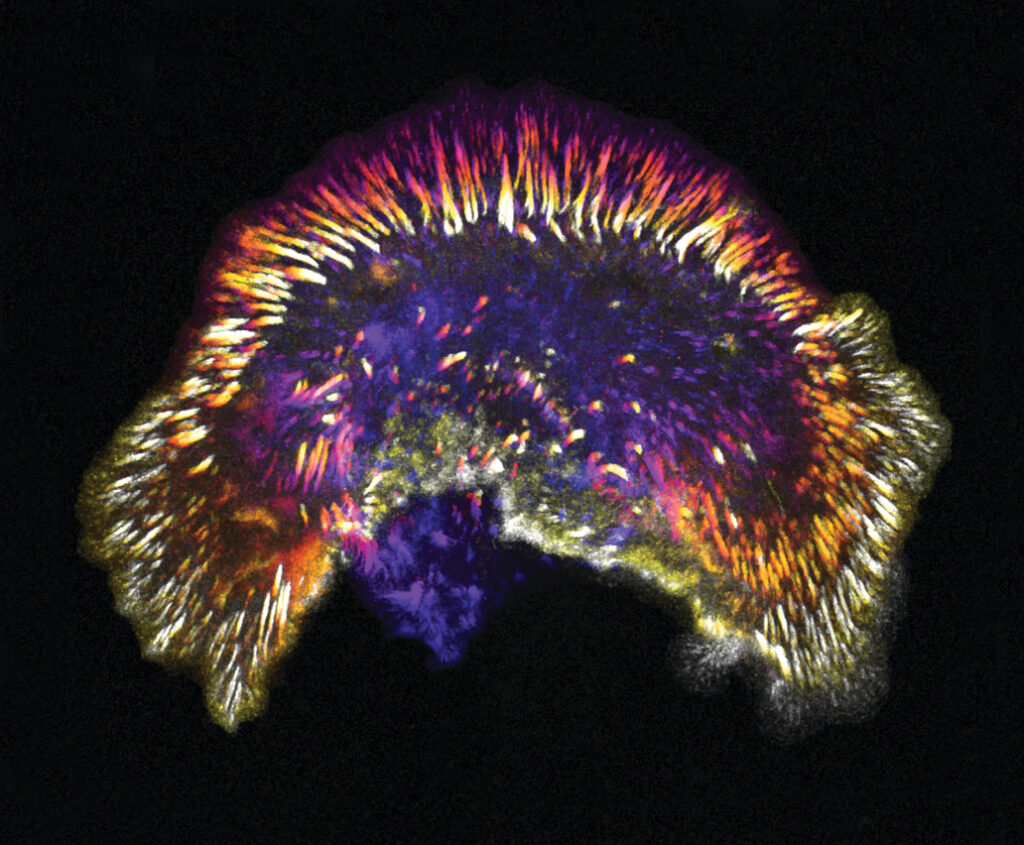

Human cells are surrounded by biological fluids like mucus and saliva that have varying degrees of thickness and stickiness. Patients with certain kinds of cancer and those with life-threatening lung diseases— including asthma, COVID-19, cystic fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)— secrete honey-like mucus that is 2,000 times thicker than normal.

Surprisingly, cells move twice as fast in this thicker liquid than they do in thinner, normal mucus. Why and how? The answer may shed light on the causes of cancer and lung diseases and help scientists develop better treatments.

Observing cells in various fluid environments, a team of engineers led by Yun Chen, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, discovered that adherent cells (cells that must be attached to a surface to grow) do not just passively experience the fluid surrounding them. Instead, they use “ruffles”—cell membranes that wave up and down— to flatten, probing the fluid around them and adapting instantly to its viscosity. The interplay between these ruffles and the fluid propels the cells to move faster in syrupy fluids than they do in thinner, water-like ones. Previously, ruffles were considered to be of little importance to the cell, akin to a human appendix.

These findings, which appeared in Nature Physics, could inspire new treatment for mucus-related illnesses, including chronic lung diseases and mucinous cancer, the deadliest subtype for lung and ovarian cancer.

High viscosity (thick mucus) can result in immune cells moving quickly into the lungs, causing excessive and damaging inflammation. In the case of cancer, high viscosity may help spread cancer cells more quickly throughout the body. Though mucus-thinning drugs exist, they currently are used to help patients breathe by coughing sputum out of their airways. Insights from this study could provide direction for repurposing these drugs to treat inflammation and thwart cancer metastasis.