A team of mechanical engineering researchers has learned that mosquitoes flap their wings not only to stay aloft but also to generate sound and to point that buzz in the direction of a potential mate. The findings could have implications for the design of quieter drones, as well as for devising nontoxic methods of exterminating the disease-spreading insects.

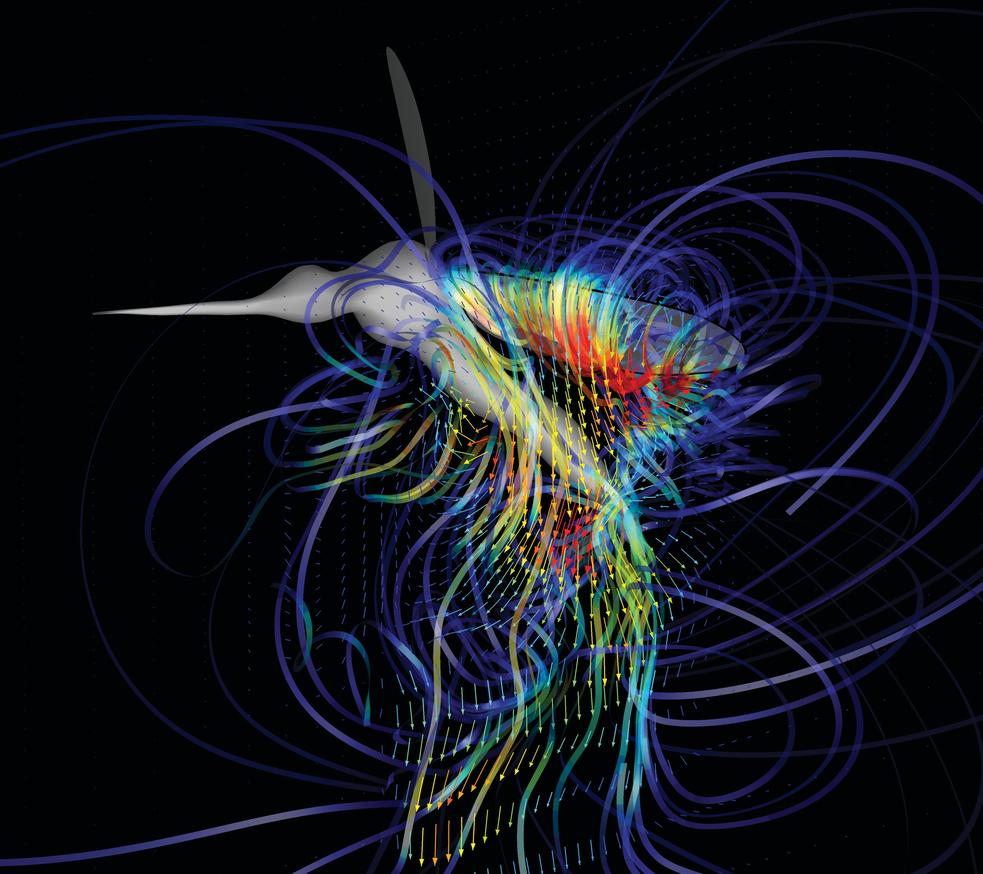

In a paper published in Bioinspiration and Biomimetics, Rajat Mittal, a professor of mechanical engineering, and Jung-Hee Seo, an associate research professor of mechanical engineering, explain the aerodynamics and acoustics of the mosquito mating ritual through computer modeling.

“The same wings that are producing sound are also essential for them to fly,” says Mittal, an expert in computational fluid dynamics. “They somehow have to do both at the same time. And they’re effective at it. That’s why we have so much malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases.”

With its high-frequency buzzing sound, a male mosquito attempts to connect with the low-frequency hum of a female. To do so, he must flap his long, slender wings at high frequencies, while also rotating them rapidly at the end of each stroke. (Yes, that annoying drill-like shrill that precedes a female’s bite is also a vibrating serenade to a male mosquito’s antennae.)

Unlike other flying insects their size, mosquitoes have adapted their anatomy and flight physiology to solve the “complex multifactorial problem” of trying to fly and flirt at the same time, Mittal says.

The team reports that both the mosquitoes’ wing tones and aerodynamic forces are highly directional and are controlled simultaneously by the insects as they pursue mates.