The kinks will no doubt be worked out— such is the nature of living in a nonstop beta-testing world. What’s really up for grabs is whether the Balaur Wall will reach its full academic and industrial potential, or whether it becomes a glorified marketing billboard. Such video walls have been installed on other campuses, with The Chronicle of Higher Education noting that admissions-types use them to essentially say, “See, we’re cutting-edge here!” or, in the Chronicle’s words, they serve “more as promotional showpieces than as spaces for academic work.”

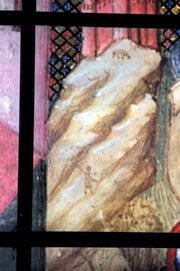

Since ancient manuscripts were handwritten and often elaborately illustrated, the Wall’s extreme zoom-in function allows students and researchers to essentially get into the mind of the scribe who drew the work.

The brains behind the Balaur Wall at Hopkins—computer science department chair Greg Hager and students in his Computational Interaction and Robotics Lab—are shooting for the latter. The Balaur’s very name (it derives from a 12-headed Romanian dragon) was chosen because it connotes the myriad ways in which the Wall can connect with people. For a teacher like Romance languages Professor Stephen Nichols, this means bringing ancient manuscripts to life in a previously impossible manner.

Traditionally, Nichols says, his students rarely saw ancient manuscripts in their original form; instead, they read paperback “critical editions,” in which a scholarly expert has provided both the English translation of the work and its significance.

But with the Wall, Nichols says students don’t need an intermediary to study a manuscript; they can instead develop their own expertise by analyzing a digitized copy of the original work. Nichols, who has been involved in digitizing medieval manuscripts for nearly 20 years, notes that the sheer size and functionality of the Wall allows students to get closer to manuscripts than ever before. In doing so, they can begin to break down the traditional teacher/ student hierarchy that both sides find increasingly limiting.

what hadn’t been seen before

on this cliff: a human figure

and small animal.

As technology has advanced, Nichols has watched digitized manuscripts go from a classroom projector to students’ computers and to their iPads. Advances to be sure, but the result is still essentially a lecturing monologue between academic and supplicant. Even if 10 different manuscripts could be brought up on 10 different iPads, students would have to pass iPads around to each other to compare texts, a chaotic proposition at best.

But the Wall allows multiple texts and their rich detail to come to life simultaneously. Since ancient manuscripts were handwritten and often elaborately illustrated, the Wall’s extreme zoom-in function allows students and researchers to essentially get into the mind of the scribe who drew the work. Blowing up a single letter to the size of a softball not only gives a visual fingerprint as to who the scribe was but could reveal elements in the drawings that change the way scholars think about the time period.

Take, for example, the issue of race. “There’s a belief that the concept of race is very recent, just the last few hundred years,” says Sayeed Choudhury ’88, associate dean of the Sheridan Libraries and director of the Digital Research and Curation Center. “Now research is showing that race may actually be represented in these manuscript images; the more evil or nasty characters appear to be drawn differently. Some facial characteristics are different, the way a nose is shaped. On a regular monitor, maybe you could just make that out. But on this thing, you get such resolution that it becomes clear. These scribes spent many, many hours on these manuscripts. For whatever reason they decided, yes, we’re going to make these characters look different.”

That such discoveries are taking place in a library setting is not an accident. Ostensibly, the Balaur Wall was to be a powerful visual element for the Brody Learning Commons, which opened last summer. But thematically, the Wall—which is subtitled “The Brody Active Learning and Usability Research Wall”—ties into the facility’s design, which fosters collaboration through openspace team studying areas and whiteboards upon which ideas can be discussed, evaluated, and expanded. Similarly, as students congregate around the Wall and manipulate, say, medieval manuscripts, they take ownership of the material in a way that’s just not possible in traditional classrooms. “Having the Wall in the library, you do away with the professor/student hierarchy dynamic and the students love it. Younger faculty, I think, are the people who are really going to pick this up and run with it. They grew up with this,” says Nichols.