Kristina Johnson’s engineering path seems as though it was destined. Her father and grandfather were both electrical engineers for the Westinghouse Corporation and first-class tinkerers. Johnson’s father, who died her sophomore year of college, fashioned his own ham radio at age 13 and pieced together an electronic keyboard during his senior year in high school—back in 1932.

Johnson exhibited signs early on that she inherited that same engineering gene. She loved math, regularly checking out math books from the library, built telegraph sets, and treasured the slide rule she received as a present. “That might have been when all the trouble started,” she jokes.

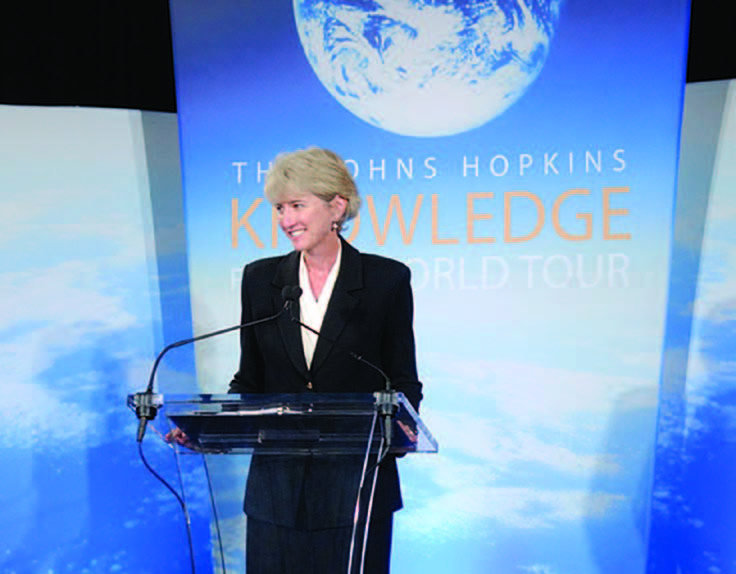

After considering a math major in college, then physics, she eventually chose electrical engineering. “It combined the best of both worlds, I thought,” says Johnson, who on September 1 became the university’s 12th provost and senior vice president for academic affairs. She is also the first woman to hold Johns Hopkins’ second-ranking position.

“All my life since college, I’ve been trying to get women and girls interested in science and engineering. It’s been a passion of mine.” Kristina Johnson

A pioneer of applications with liquid crystals, Johnson holds more than 40 patents and is the co-founder of several start-up companies. She comes to Hopkins from Duke University’s Pratt School of Engineering, where she served as dean since 1999—also the first woman at Duke to hold that position.

Johnson was born in Webster Groves, Missouri and raised in Denver, Colorado. Her road to Johns Hopkins University has been an impressive one. As a senior in high school in 1975, her science fair project that used holography to map the growth of a fungus won a city and state contest and ended up garnering first prize in the Department of Army Awards and a second prize at the International Science and Engineering Fair. The editors at the Denver Post took notice, electing her to the paper’s annual Hall of Fame.

Johnson enrolled at Stanford University on a Westinghouse Scholarship and graduated with distinction in 1981 with both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in electrical engineering. After earning her PhD at Stanford in 1984, she spent two years on a NATO post-doctoral fellowship at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, before joining the faculty at the University of Colorado. During her tenure there (1985 to 1999), she earned a National Science Foundation Young Investigator Caree r Award and worked her way up to full professor before leaving for the top engineering post at Duke.

Johnson has worked on microdisplays for high-definition projection televisions, a 3-D holographic puzzle, HDTV color separations, and optical symbol processing. Her company ColorLink, which she co-founded and sold in 2007, worked on circularly polarized 3-D technology for animated movies such as Chicken Little, Polar Express, and Monster House.

She is perhaps best known in research circles for pioneering work in the field of “smart pixel arrays,” which has applications in displays, pattern recognition, and high-resolution sensors, including cameras.

The new provost’s life does not start and end with her work, however. A sports enthusiast, she started women’s lacrosse at Stanford and also played field hockey. She has a red belt in tae kwon do, played for Ireland’s President’s Eleven ladies cricket team, and rides horses recreationally whenever she can.

She’s also very passionate about involving young people, in particular women, in science. In 1990, she partnered with a television weatherman in Denver to create a 10-part educational series called Physics of Light. The highly successful series, geared toward 5th- to 8th-graders, aired on a local NBC-affiliated station and was later distributed to more than 500 schools throughout the Rocky Mountain region.

“All my life since college, I’ve been trying to get women and girls interested in science and engineering. It’s been a passion of mine,” says Johnson, who was inducted into the Women in Technology International’s Hall of Fame in 2003. A year later she received the Achievement Award, the Society of Women Engineers’ highest honor.

She is quick to point out that her advocacy extends beyond gender lines. “I’m an advocate for all people—[including] men and minorities,” Johnson says. “In my work with students, I want to see each individual grow and succeed to the best of his or her ability.”