When 11 engineering seniors look at the flat, black roof of Ames Hall, they see the potential to make the world a better place. The fact that the roof membrane is old and scheduled to be replaced next year just makes it that much more appealing.

The roof is currently home to a couple of potted corn stalks (placed there by Professor Grace Brush to gather pollen samples). But the students envision it covered with the tiny white blossoms of sedum album, the delicate pink of sedum spurium, and many other colors of the more than 400 species of leaf succulents that comprise the sedum genus.

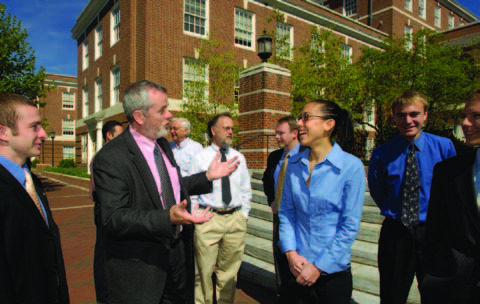

On May 8, 2007, the students presented this verdant vision for Ames Hall to university leaders, including Whiting School dean Nick Jones and Davis Bookhart, Johns Hopkins’ manager of energy management and environmental stewardship. The “Ames Hall Green Roof Proposal” is the culmination of their semester-long senior design project sponsored jointly by the departments of Civil Engineering and Geography and Environmental Engineering (DoGEE).

The project, originally proposed by Bookhart, charged the students with investigating the viability of covering the flat, rubber membrane portion of Ames Hall’s roof with a carpet of plants, one way that the university could demonstrate environmental leadership by embracing smart, sensible, and creative actions that promote sustainability. “This was an excellent way to teach our students about important changes happening in building design,” says Ben Schafer, an associate professor of Civil Engineering. “Especially the movement toward sustainability.”

The goal behind green roof projects like this one (which are now being embraced in cities spanning the country) is to offer protection against ultraviolet degradation, mechanical damage, and temperature extremes while simultaneously providing insulation that lowers heating and cooling costs for buildings and reduces the “urban heat island effect.” Additional benefits: Garden roofs contribute to better air quality, substantially reduce storm water run-off (which helps to mitigate sediment erosion), and offer urban meccas for birds, bees, and butterflies.

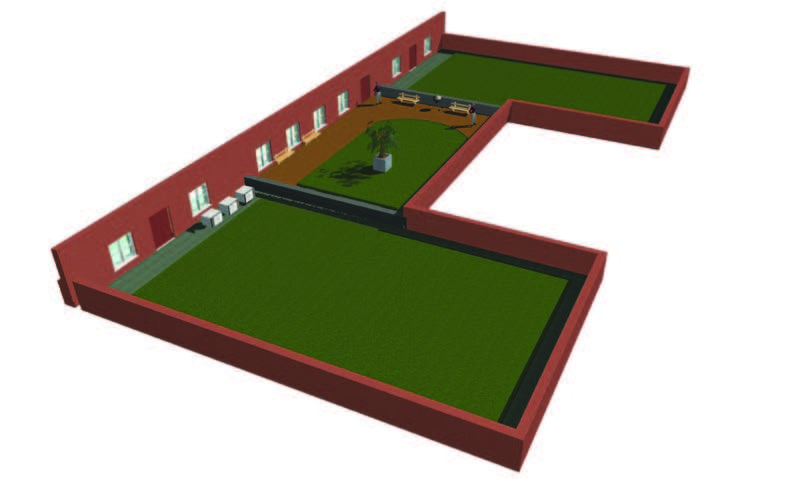

The students’ final proposal combines “extensive” and “intensive” approaches. The two sections over the building’s wings would be extensive, with a low soil weight and plants capable of surviving under a broad range of conditions, serving as a learning lab for students. The center section would be semi-intensive, with a single tree, a plastic deck, gravel paths, and benches—an area suitable for gatherings of students and faculty.

To get to this point, the students worked in groups and tackled different aspects of the project including water management, stakeholder interests, the structural capacity of the roof, and a life cycle analysis evaluating the total environmental costs and benefits of the project. A structural analysis of the building determined how much weight it could support. The amount and quality of the roof’s water runoff was calculated and drainage options were considered. The students looked at the building’s thermal performance, selected different types of plantings, and considered the insulation benefits a green roof could offer. In addition, they balanced all of these factors against the admittedly higher cost of “going green.”

Ultimately, they concluded that although the initial investment to build a green roof would be $234,825 ($137,826 more than the cost of simply replacing the existing rubber membrane), the school would realize approximately $31,721 in cooling and storm water fee savings over the green roof’s predicted 40-year life span. Additional benefits include decreased air pollution and providing an example of sustainable design to the Hopkins community and beyond—not to mention, the green roof can be expected to last twice as long as the conventional roof planned for Ames Hall.

“This is the first time our departments have done a collaborative design project together and I think we met all of our objectives,” says Schafer. “The students worked together and learned how to do practical design that makes financial sense.” Adds DoGEE Professor Peter Wilcock, “The first design concepts they came up with were far too costly, but they were able to shift gears. They came up with a realistic design that could actually be built.”

The students’ plan is now in the hands of Dean Jones and the Office of Facilities Management. “I would love to say that our design will be implemented,” says civil engineering design team member Emily Roche. “But if nothing else, I hope our presentation convinced the school that these kinds of adaptations are possible—that it can be done.”