Admit? Deny?

When “March Madness” descends on Admissions at Johns Hopkins, this portentous question becomes all-consuming. We take you inside Garland Hall, in the stomach-churning weeks leading up to the big mail drop on March 28, as Hopkins admissions experts grapple with crafting the “perfect” freshman class.

March 27 There is a controlled urgency in the air and a sense of organized chaos. It seems that everyone is talking at once, both staff and students, about which bins hold envelopes ready to be mailed, envelopes needing stamps, and envelopes needing to be sealed. An undergraduate hustles past with a slice of pizza in one hand and a stack of postage slips in the other. A staff member sits on the floor, her shoes kicked off and a bin of letters in her lap, applying $4.05 worth of postage to 3,588 large envelopes.

The 40 or 50 people here tonight in the basement of Garland Hall are packed into two long hallways and a small, windowless room. Plastic blue bins, crammed full of U.S. Priority Mail envelopes, line both hallways, are stacked three deep in mail carts, and cover all available counter space. What each envelope contains, along with several pieces of supplemental materials, is a sheet of paper coveted by 14,842 high school seniors: a Johns Hopkins University acceptance letter.

It’s 6 p.m. on Tuesday, March 27. Acceptance letters—and rejection letters—will go out in the morning.

“The Ivies post decisions online on Thursday and we want to beat them,” is one staff member’s explanation of tonight’s mad, after-hours rush. “We’ve been waiting all day for our director to be satisfied with the class,” another explains. “Nothing’s final ’til these letters hit the mail.”

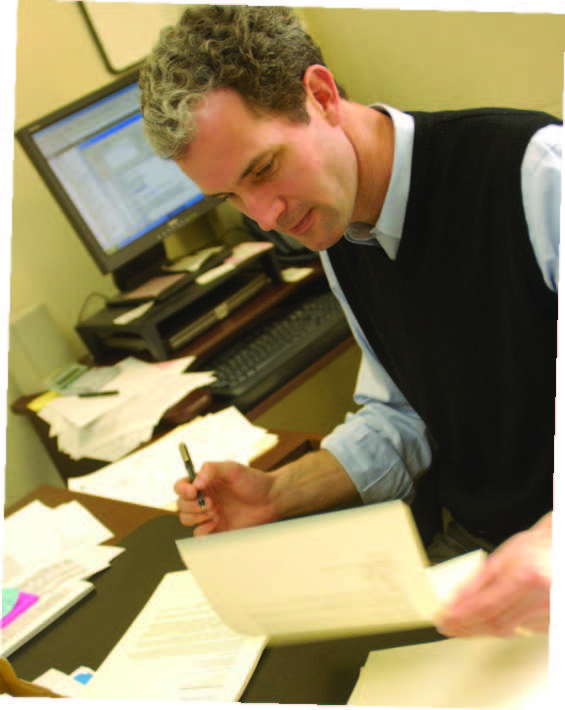

In fact, their director, John Latting, hadn’t made his final decisions until late that afternoon. What kept him fretting all day, locked in his office, was the handful of applications teetering on the edge of acceptance or denial.

Latting, Hopkins’ Director of Undergraduate Admissions, is charged each year with shaping the next freshman class. “A perfect freshman class,” he says, “is one in which every single student has a deeply rooted desire to learn, motivation, and a sense of purpose. We won’t accept kids who are simply going through the motions, no matter how smart they are. They must be open minded and willing to change.”

The scene in the mailroom draws a stark contrast to the admissions process itself—a carefully orchestrated process in which every single application is individually evaluated. Part of the goal is to have 405 freshman engineering students walk onto the Homewood campus this fall. Of the 14,842 students who applied to the university, 3,916 applied to the Whiting School, and Latting has already accepted 130 of them as “early admission” for engineering.

The competition for the remaining 275 spots is intense. Last year, the undergraduate students admitted to Hopkins had an average high school GPA of 3.69, SAT math scores between 660 and 760, and SAT verbal scores somewhere between 630 and 730. Eighty percent of freshmen were ranked in the top 10 percent of their high school class. These are the best of the best. Not surprisingly, these are the students who are also applying to schools like MIT and Harvard. Those whom Hopkins accepts will, most likely, receive attractive offers from other schools, too. So, to enroll 405 engineering students, Latting and his admissions team have figured out that they must offer admission to 1,405.

“But we don’t want 405 biomedical engineers,” says Bill Conley, dean of enrollment and academic services, of the Whiting School’s most popular discipline. “We want 100 biomedical engineers and the other 305 should be proportionately distributed across the other departments.”

Quite a formidable challenge for the admissions staff, enough to keep Latting and company’s stomachs roiling throughout winter and into spring. What factors shape their evaluation process? To begin with, they don’t just admit those with the highest test scores. “Talent is dispersed across all different types of people, who have different cultures and backgrounds,” Latting says. “Different perspectives make a good incubator for innovative thinking. If you value innovation, then diversity is what you need.”

Conley points out that this effort to shape the class represents the most fundamental shift in the admissions process in the past 25 years. “We used to think we should simply admit the smartest kids and let an invisible hand distribute them,” he says. “We can’t do that anymore.”

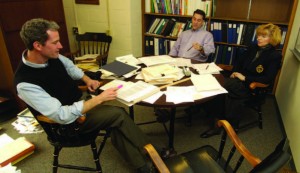

So, to arrive at their desired outcome, Conley, Latting, and their team of admissions counselors and staff immerse themselves in an in-depth process that culminates in an admissions version of March Madness. Counselors have spent two months reviewing every application, and the best survived to be considered by multiple committees. The process is an individualized one that does not occur at every college or university. And though admissions at Hopkins is viewed as an art, not a science, this is where things get complicated.

March 14 Two weeks earlier, it’s late in the morning and admissions counselors Daniel Creasy and Mark Butt sit in their Levering Hall office. Poring over applications, they face the first hurdle of the March process: guaranteeing that enough engineering students are offered admission so that at least 405—but no more—will accept.

Predicting such results requires a complex method, and the admissions office has looked close to home for expertise. John Wierman, a professor in the Whiting School’s Applied Mathematics and Statistics department, has created a formula that uses statistics and logic to rate various sections of an application and determine the probability that the applicant, if offered admission, will accept. Dubbed “The Wierman Model,” the algorithm has been used in Hopkins’ admissions process for more than a decade and takes into account such factors as the applicants’ areas of study, whether they’ve visited campus or not, what region they’re from, financial aid status, and just about every aspect imaginable that could affect the probability of their saying yes to Hopkins.

“One of the most interesting factors is what state they live in,” says Wierman. “We’ve found that those who live between 200 to 400 miles away have the highest rate of acceptance. It’s as if parents think that if it’s over 400 miles from home, it’s too expensive to get there frequently, and the kids think just the opposite: 200 miles is far enough from home that they feel like they’re out on their own.”

The Wierman Model is reformulated each year to reflect changes in the marketplace, such as the recent trend of students applying to seven or eight schools instead of the three or four that previous generations did. (While the “shotgun” approach might increase the number of schools a student can potentially choose from, it decreases Hopkins’ success rate for recruitment.) Latting uses the program about every two weeks during his decision-making process. It helps him avoid admitting 1,405 students, in the hopes of 405 accepting, and facing the nightmarish situation of having every one of them—or none—accept. “If we’re wrong on our numbers,” Wierman says, “we could end up having 200 people doubled up in dorms or the opposite and not enough.”

With an application deadline of January 1, admissions counselors began reading applications back in December. Throughout January and February, the team of nine read each of the nearly 15,000, selecting the best to be passed on for review by small committees. By now, in mid-March, the counselors and committees have trimmed the stacks to 4,000. About 1,500 of the remaining applications are for Engineering and the day’s goal is to cut 100 of them.

The easiest place to look is the Biomedical Engineering (BME) Department. As the top ranked program in the country, BME is the only department that requires students to apply specifically by major and does not accept transfer students. The counselors know that the chances that a BME applicant will come to Hopkins if he’s been declined BME are slim. So Creasy and Butt scrutinize the stacks of applicants with BME elected, looking for those who aren’t strong enough for acceptance into this highly competitive program.

The data sheets the two men pore over are three feet wide, requiring them to use yardsticks to follow the 50 horizontal data fields that stretch across the page for each student. “Here’s a 3.7 from Rhode Island, decent transcript, no extracurricular activities,” Butt says. “Test scores are low, he wants BME—but he’s not going to get it and his second choice is Arts and Sciences.” After a few more minutes of back and forth, it’s decided to leave the application in the admit pile—for the time being. The duo moves on to the next applicant.

“This kid has a 550 Math SAT… he needs to be cut. This one is from Greece, passed the TOEFL, and has high math scores… he can stay for now. Do you know where Santa Maria High School is? What do we know about it?” Butt asks, searching for a reason to overlook the applicant’s low test scores. “Well, she’s first generation… I think she’d add a neat perspective. Let’s keep her for now.” The team will reconsider her in the next round of reviews.

The truth of the matter is that many students apply to BME because it’s related to medicine and they see it as a steppingstone to medical school. But, there’s a chance that a student who doesn’t succeed at BME won’t stick with engineering. Most likely, that student will choose to transfer majors to a non-engineering/medicalrelated subject such as biology or chemistry. “We call them ‘migrants,’” Butt says, “and having students swap between schools is an administrative nightmare.” Not only that, but if it happens in excess, it upsets the balance of Latting’s carefully selected freshman class. BME applications are specifically examined for this risk.

March 21 Deny and waitlist letters—all 11,254 of them—are being printed in preparation for the March 28 mass mailing. Even though two printers churn them out, it’s several hours before they can be hand-stuffed into envelopes: single sheets of cream-colored paper in matching—disappointingly slender—envelopes.

The Garland Hall rooms of the Admissions Office are teeming with counselors and staff, gathered around the office’s 21 filing cabinets. The metal cabinets, each five drawers tall, contain the folders for every applicant this academic year. With so many responses being mailed, it is imperative to continually confirm that every applicant will be mailed the correct letter. As the mailing draws closer, teams conduct “drawer checks.” As one person inches through the master folders in the filing cabinets, calling out a name and a decision, another thumbs through a bin of deny and waitlist letters, confirming they are correctly matched. Letters for accepted students haven’t been printed. There are still a few of those decisions yet to be made.

Two days later, on March 23, Latting sits behind the closed door of his office, struggling over the final questionable files. There are about 40 left to consider, and all have agreed that they have strengths and weaknesses that make the decision very difficult. The admissions counselors have all but thrown their hands in the air and left Latting to make the final yes or no.

Some of the applications have already been deemed denies, but someone—a counselor or faculty member—has asked Latting to reconsider. However, most applications in this group were leaning toward accepted status, but there was something questionable: there’s a disciplinary problem, one applicant is younger than average and Latting worries he’s not yet mature enough to handle college, and one transcript shows that the student’s grades dropped in the final year of high school.

Latting is also factoring in how much financial aid he can give to international students (federal loans are scarce and schools usually reserve the majority of their aid for U.S. citizens), Baltimore Scholars (a full tuition scholarship to accepted students from the Baltimore City public school system), and children of employees. In one case, a student has refused to submit the application fee or a fee waiver and Latting is scouring the application to figure out if there’s a financial hardship that the student might be embarrassed about.

On the other side of Latting’s door, the admissions staff and student volunteers are hurriedly doing another round of drawer checks.

In the middle of all the activity, Butt walks in with a list in his hand. “Is that it—do you have it?” Creasy asks, excitedly. He’s referring to the list of 12 finalists for the Westgate Scholarship.

In the middle of all the activity, Butt walks in with a list in his hand. “Is that it—do you have it?” Creasy asks, excitedly. He’s referring to the list of 12 finalists for the Westgate Scholarship. Thanks to a generous donation made by engineering alumnus Kwok Li ’79, who endowed a fund in honor of former Electrical Engineering faculty member Roger Westgate (see p. 10), each year counselors can nominate students for a full four-year scholarship. It covers the entire tuition ($35,900 in 2007– 08) and is purely merit based. Both Creasy and Butt nominated students.

“The purpose of the Westgate Scholarship is to bring the very, very best engineering students to Hopkins,” says Andrew Douglas, the Whiting School’s associate dean for academic affairs, who oversees the Westgate selection process. “It benefits Hopkins because of the dynamism these students bring to the campus— from leadership at the university to becoming wonderful alumni.”

What Douglas means by, “the very, very best,” are students who don’t just excel in the field of engineering, but who have above average intellectual engagement, an excitement about research that is unparalleled among their peers, and a unique perspective on the world around them. There’s a strong track record for past recipients: One served as class president and went on to Harvard for medical school; another was student council president and is now in medical school at Yale.

Of the finalists this year, one student scored an 800 on the SAT, the SAT I, the SAT II, the Verbal SAT, the Math SAT, and the Latin SAT, a 760 on the Biomolecular SAT, and a 750 on the Physics SAT. What impressed faculty most was the applicant’s research conducted in high school; it focused on computer models of accreting neutron stars. But though his test scores are high, so is his parents’ household income, weakening the allure of the full-ride aspect of the Westgate. For him, the tuition break may not succeed as the carrot it was designed to be.

However, another finalist may very well appreciate the break in tuition. As a non-U.S. citizen, her access to financial aid is limited. According to Douglas, this remarkably gifted student has achieved what very few have. “You just look at her and wonder how she managed to get from where she was to where she is now,” he says. Her SAT scores and grades are high, but what the faculty committee responded most positively to are her communication and mediation skills, extracurricular activities, overall character, resilience, and ability to not only succeed herself but her potential to lead others. “With her background and her accomplishments,” Douglas says confidently, “she would make an exceptional bridge-builder among students.”

MARCH 27

While Douglas and the team of faculty who conduct on-campus interviews with each candidate decide which of the 12 applicants to offer the distinguished Westgate, Creasy and Butt are facing the reality of Latting’s decisions. It’s now the late afternoon of March 27. All decisions have been made.

“One of my kids was cut,” Creasy says of a student he had gone to bat for. “I just wanted to go to John and say ‘please….’ Honestly, there are very few things I’ve done in my life that are this emotional.” But, however much a single counselor likes a particular student, each knows that Hopkins can only admit so many and that the 10 percent of total engineering applicants who will end up at the Whiting School can’t include everyone.

In the basement of Garland Hall, staff, counselors, and student volunteers proceed through the bins. The floor is littered with strips of discarded paper from postage slips and postage envelopes, the room hums with chatter, and blue bins are whirled past, headed for the mail carts.

“Here’s one of mine!” admissions counselor Jeremiah Shepherd exclaims to himself as he spies a name on one of the envelopes. “It’s cool when you can follow someone through the whole process,” he says. “From meeting them at a school visit, reading their application, and then seeing them in this bin, as opposed to the ‘denied’ pile—it’s all very exciting.”

As the clock ticks well past dinnertime and as envelopes are stuffed, given postage, and sealed for the morning mailing, some 14,842 high school seniors eagerly await their verdict from Johns Hopkins.

Says Conley: “My dream for Johns Hopkins is that when a graduate tells someone that they went to school here, the reply is no longer, ‘Oh, did you want to be a doctor or a scientist? Was it brutal? Was it cut-throat?’ but that the response becomes, ‘Wow, you must be a really interesting person.’ That will be the barometer to show me that we’re getting the right distribution of students; that we’re achieving the perfect freshman class.”

MARCH 28

POSTSCRIPT Days after the May 1 due date for all acceptance responses, Latting and his staff feel great about the results of their efforts. Although 424 students accepted for the 405 engineering spots—just a bit above the target— it is proof that Hopkins Engineering holds an even stronger position than in years past

Because the Krieger School pulled in 758 students (goal: 800), Latting has ended up with 23 open slots for Arts and Sciences. “This is just ideal,” he comments a few days after the deadline. “We can now go to the wait list, which, though you don’t want to use it massively, is always good to use a little. It enables us to meet specific needs of the class, and it’s encouraging for future students to see that the waitlist isn’t a hollow offer.”

Latting’s only area of concern is the unexpected bounty of BME student acceptances. At 140, it is well over the target of 100, telling Admissions that BME at Hopkins is more popular than ever and that they need to rethink their estimates for next year. It also gives the BME Department four months to prepare for 40 extra students, the kind of challenge that can never be fully expected, no matter what steps are taken or what predictive models employed.

Hopkins Interactive Today, more than ever, high school students are turning to the Internet to get information about prospective colleges. The Hopkins Admissions Office offers a new website, called Hopkins Interactive, which includes Hopkins Insider, “behind-the-scenes access” to the Admissions Office; Hopkins Interactive Guest Blog, which features different straight-talking students each week; The JHU Fun Blog, which uses “traveling gnomes” to highlight the fun to be had at Hopkins; and This Week@ Hopkins, a weekly Hopkins entertainment events listing.

Such sites not only help to humanize the university and the admissions process, says John Latting, they convey the idea that college life at Hopkins is fun, vibrant, and relaxed. “It’s showing that Hopkins is a small, close-knit school where students have lots of freedom to pursue their interests, where they can explore, and where they are surrounded by interesting people,” he says. Visit http://apply.jhu.edu/hi/blogs/blogs.html.