The founding principles of Engineering’s first dean still guide the Whiting School today.

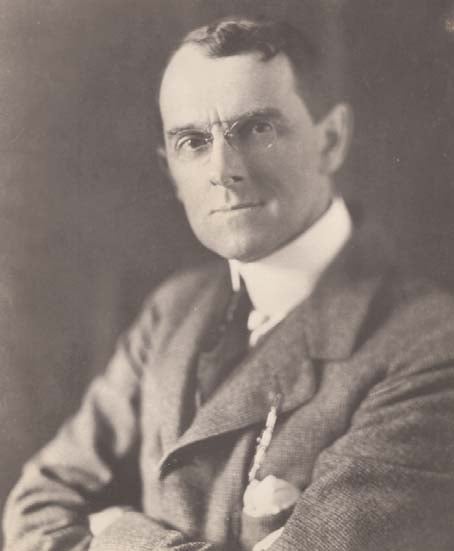

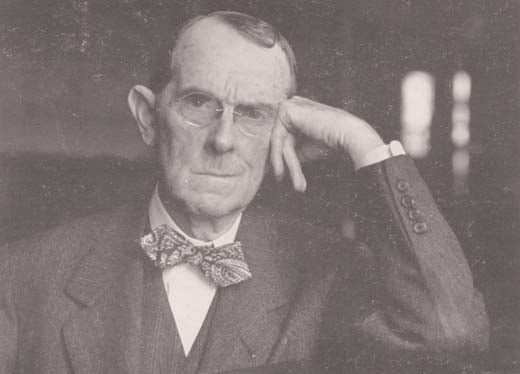

He was a man of power—in more ways than one. In the course of a professional career that literally spanned the first half of the 20th century, John Boswell Whitehead made enormous contributions to the field of electrical engineering. In an era when there was a pressing need to expand the use of higher voltages, his research earned him international honors.

However, his most lasting creation was not to be in science but in education, as one of the founders and first dean of Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University. Moreover, it was Whitehead’s own vision of the new department—as a center for “advanced professional instruction, experimental research, and in participation in national societies”—that still drives the Whiting School of Engineering’s continued momentum today.

POISED FOR A NEW CENTURY OF INVENTION

Born in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1872, Whitehead grew up in an era of explosive scientific discovery that in turn ushered in a new century of invention and innovation. When Whitehead was 3, Bell made his first telephone call; when Whitehead was 8, Edison’s 16- watt light bulb blinked on. By the time the 17-year-old Whitehead arrived at Johns Hopkins in October 1889 to begin his undergraduate work, the camera and the automobile had also appeared. It was time of dramatic possibilities, especially for a young man with an interest in electricity.

The freshman actually had come to Hopkins intending to study history and politics. However, by chance, a high score on his entrance exams allowed Whitehead to skip a required course in German and instead take the only elective left that fit his schedule—Physics 1. Through this class, he gained access to the University’s Physical Laboratory, led by the famed physicist and department chair, Henry A. Rowland. It was also in this department where a new course of study had been launched in 1886, taught by a former student of Rowland’s, Louis Duncan. The two-year Proficiency in Applied Electricity program was intended to train students for certification in engineering positions, especially within the railroad industry. Duncan saw the course as teaching “electricity as a science and in its practical application.”

Once Whitehead learned of Duncan’s course, there was no further pursuit of history. As Whitehead later wrote, what led him to shift to studying applied electricity was “contact, even remote, with these activities, and early vision of an intimate relationship and community of interest between pure research and the application of science.” He received a BE certificate in 1893, the year the World’s Fair in Chicago illuminated electricity as the pathway to progress instead of something to be feared.

A GROWING “COMMUNITY OF INTEREST”

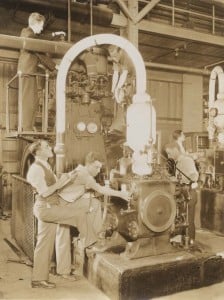

In Pittsburgh, Whitehead began his first job in the shop of Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co., which was building generators and transformers for a Niagara Falls, New York, power station. He then worked on-site as the plant began operations. Whitehead returned to Hopkins in 1898, perhaps finding this “community of interest” to be an appealing reason. That year, he earned his BA from Hopkins and became an instructor in applied electricity. It was a momentous decision. Despite lucrative offers from private industry later in his life, Whitehead would remain at the University for the rest of his 44-year career. His expertise was often sought: on how to safely put electric cables underground in Baltimore, on how to shield high-voltage lines from lightning, and on why the Hindenburg blimp caught fire.

After receiving his PhD in physics from the University in 1902 and a promotion to a full professorship in 1910, Whitehead became involved in the organization of a new educational initiative—one designed to dissuade young men from leaving Maryland to study at technological institutes elsewhere. Under “The Technical Support Bill” from the state legislature in 1912, Hopkins received funding to create “a school or department of applied science and advanced technology” and to establish 129 scholarships of free tuition to “worthy men of this State.” Through the efforts of Whitehead and others, the new Department of Engineering in 1913 opened its doors to its first students, including the legendary Abel Wolman ’13 A&S, ’15 (profiled in the Spring 2002 issue).

In 1917, Whitehead briefly left his teaching post to serve in World War I. Having been an ROTC student at Hopkins, he was commissioned as a major in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and he engaged in research work for the Naval Consulting Board to develop methods to detect enemy submarines. Returning to Hopkins after the war, he oversaw the transition of yet another stage of growth for his beloved department. In 1919, in acknowledgment of its steady growth and rising reputation, the Department of Engineering was recast as the School of Engineering, and Whitehead was named its first dean.

“HE TREATED STUDENTS AS HIS EQUALS”

Highlights of “The Whitehead Years” at Hopkins

1889 John Boswell Whitehead enters the Johns Hopkins University as an undergraduate.

1893 He is granted a BE (Proficiency in Applied Electricity certificate) from Hopkins.

1898 After earning a BA, he joins the Hopkins faculty as instructor in applied electricity.

1902 Granted a PhD from Hopkins.

1910 Named professor of Electrical Engineering.

1912 Becomes active in the University’s efforts to create a department of “applied science and technology.”

1913 Hopkins accepts its first class of students into the new Department of Engineering.

1914 The first Engineering building on the Homewood campus—Maryland Hall—opens its doors.

1914-1915 First Engineering undergraduate degrees awarded.

1919 The Department of Engineering is renamed the School of Engineering; Whitehead becomes its first dean in 1920.

1928 The University establishes an Engineering major for students who want to earn a degree through night courses.

1934 The American Council on Education names the Electrical Engineering department as one of the three best in the country.

1937 The School by this time has graduated more than 1,000 students. An engineering show’s exhibits on campus attract 12,000 visitors.

1938 Whitehead is succeeded as dean by William B. Kouwenhoven.

1942 Whitehead retires from Hopkins at age 70 as professor emeritus, but would return to conduct research almost until his death in 1954.

“It has long been my feeling that the School of Engineering can best support the ideals and standards of the University through the development of advanced professional instruction, experimental research, and in participation in national societies whose purpose is in the elevation and advance of the profession of Engineering.” DEAN WHITEHEAD IN A 1930 LETTER TO JOSEPH S. AMES, PRESIDENT OF JOHNS HOPKINS

A THREE-PART VISION OF GREATNESS

During his 18-year tenure as dean, Whitehead can be credited for introducing many of the guiding principles that still inform the character of the present-day School. These principles can be summed up by Whitehead’s own three tenets for the School of Engineering, as a place where “advanced professional instruction, experimental research, and in participation in national societies” can flourish.

Throughout his time at Hopkins, Whitehead sought to reinforce the School’s reputation for “advanced professional instruction.” By expanding programming, introducing new departments, and securing the best minds as researchers and teachers, he maintained a constant focus on improving the quality and scope of educational opportunities in engineering, both on the undergraduate and graduate level. The School regularly invited professional engineers from outside the University to deliver lectures to students— a tradition that began even before World War I. Among the topics presented during 1916-17 were ones resonant even today: “The Operation of a Hydro-Electric Plant,” “Rapid Transit Problems in American Cities,” and “Some Things Engineers Should Know Concerning the Rudiments of Corporate Finance.”

The School’s solid emphasis on “experimental research” leading to practical industrial applications was a constant during the Whitehead years. The dean himself was renowned for his work in high-voltage insulation, and received his first Montefiore Prize for his invention of the corona voltmeter, a device that employed the properties of air as a standard for high-voltage measurement. By the 1930s, Whitehead had guided students and colleagues into large-scale research projects funded by the National Electric Light Foundation, the Utilities Research Commission of Illinois, and other national groups. Research dealt primarily with the pressing issue of how to improve the current and voltage capacity of high-voltage underground cables, used to carry large amounts of electricity over long distances.

Extending the School’s professional influence through “participation in national societies” was yet another Whitehead priority. At the dean’s urging, Engineering faculty served on a spectrum of local, state, and national commissions, while organizing professional conferences and playing active roles in professional societies. As early as 1919, the new School of Engineering hosted the annual national convention of the Society for the Promotion of Engineering Education. By 1921, the School established the Maryland Alpha chapter of Tau Beta Pi, the national honorary fraternity of engineering. And Whitehead set an example himself by serving as president (1933-34) of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

The dean also promoted a high degree of community involvement through faculty consultations on local projects, including sewage disposal, industrial smoke abatement laws, and underground electric cabling for the railroads. The School even played a major role in the planning and supervision of the Homewood campus buildings and roads, as well as the heating and power plants. In his personal life, Whitehead took a keen interest in music. He and his wife, Mary Ellen, had three daughters.

RETIREMENT LAUNCHES A MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT

Whitehead turned over the reins of the deanship in 1938 to his Electrical Engineering colleague, Dr. William B. Kouwenhoven (profiled in the Fall 2002 issue), and in 1942, he retired from teaching as professor emeritus. But his quest for knowledge was far from over.

Just eight months after his “retirement,” Whitehead, then 70, was invited by Hopkins to direct a new, critical research project for the Air Force. Although the study in the field of high-frequency dielectric heating was outside of his specialization of low-frequency insulation, he immediately took on the long-term project. He completed the research shortly before his death in 1954. It was one last accomplishment in a series that stretched back half a century, powered by the vision of a man who devoted his life to a single goal, as he expressed it, “The University, the faculty, all of us are here for one purpose—so that young men can be educated.”

“He awakened rather than slaked a thirst in his students, encouraged inquiry, cradled curiosity, stirred the imagination.” Henry L. Strauss ’17, speaking of John Boswell Whitehead at the 1948 dedication of Whitehead Hall

THE BUILDING THAT BEARS HIS NAME

In 1948, the new building constructed to provide more space for the rapidly growing post-war Engineering program was dedicated in honor of John Boswell Whitehead. It is the first building the Johns Hopkins University named for a living individual. Rather fittingly, the Homewood campus power plant is connected to Whitehead Hall. Today, Whitehead Hall’s offices include those of the Whiting School’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics (formerly Mathematical Sciences).

HONORED THROUGHOUT A LIFETIME

In his exceptional career as an electrical engineer, educator, and innovator, John Boswell Whitehead received an impressive number of professional awards and honors, including:

- the Triennial Prize of the Montefiore Electrotechnic Institute of Liege, Belgium (1922 and 1925), honoring the best original work in the technical application of electricity;

- the Medal of the University of Nancy, France (1927);

- the Franklin Institute’s Elliott Cresson Gold Medal (1932);

- the Medal of Meritorious Achievement of the Advertising Club of Baltimore (1933);

- and the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (1941). The Institute’s highest award honored “his contributions to the field of electrical engineering, his pioneering and development in the field of dielectric research, and his achievements in the advancement of engineering education.”

- A member of Phi Beta Kappa, the National Academy of Sciences, the National Research Council, French Society of Electricians, Tau Beta Pi, and Delta Phi, he also was a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (he served as president in 1933-34), and the American Physical Society.

- The author of more than 100 papers and articles published in scientific journals, Whitehead also published four books: The Electric Operation of Steam Railways (1909), Dielectric Theory and Insulation (1927), Impregnated Paper Insulation (1935), and Electricity and Magnetism (1939).