While his kindergarten contemporaries were stacking Lego bricks, Jacob Heisler was building electronics. With one grandfather working in the energy industry and the other for IBM, technology was in his blood. “Between the two of them, they had me building a lot of circuits and learning how to solder,” remembers Heisler. Those early skills stuck with him, leading to his first job at age 12 in his family’s microelectronics manufacturing business in York, Pennsylvania—a role he grew into over the years, ultimately serving as the company’s engineering manager until 2024.

Now a student in Johns Hopkins’ Engineering for Professionals program, Heisler is pursuing a master’s degree in electrical engineering with a focus on solid-state devices. At the same time, he is running his own venture: Heisler Semiconductor, a prototyping and design for manufacturing firm he launched in July 2024. Early support from his University of Maryland professors and UMBC’s SCALEUP Maryland accelerator proved critical, with both institutions becoming some of his first customers. In just over a year, the company has earned the trust of universities, startups, and military contractors, bringing in about $20,000 in monthly sales.

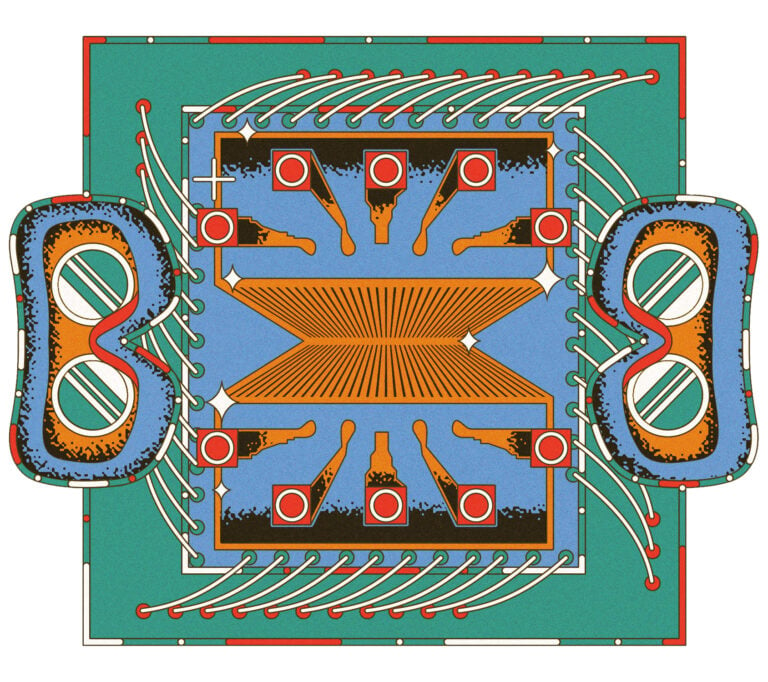

“The average person interacts with 1,000 semiconductors every day without realizing it,” Heisler explains. Semiconductors— materials like silicon—allow electricity to be controlled with extreme precision, making them the foundation of microchips that power everything from smartphones to solar panels.

Much of the U.S. semiconductor industry was outsourced overseas in the 1980s, particularly to Taiwan and other parts of Southeast Asia. Recent legislation, including the CHIPS and Science Act, aims to bring more manufacturing back to the U.S. But large West Coast firms dominate the market, leaving smaller companies needing microchips underserved.

“We work with universities and startups that need niche, one-off prototypes. If that one sample doesn’t function, their budget is gone and the project ends,” says Heisler. “A lot of organizations wouldn’t put in the care and effort needed to make these products successful.” He says Heisler Semiconductor differentiates itself by offering hands-on partnerships, competitive pricing, and integration into clients’ supply chains, ensuring a smooth transition from prototype to production. The approach has already garnered repeat business, from companies designing products ranging from communications systems to wearable medical devices and virtual reality goggles.

Despite his technical background, Heisler knew he needed to strengthen his business skills. At the suggestion of Megan Howie, Johns Hopkins Engineering’s senior associate dean of corporate and global partnerships, he applied to the Pava Marie LaPere Center for Entrepreneurship’s Fuel program, a venture accelerator for student entrepreneurs, designed to help committed ventures get market/investor ready. The program provided training, networking, and mentoring from legal and financial experts, helping Heisler hone critical skills just a few months after Heisler Semiconductor’s launch.

“We worked closely with Jacob on refining his storytelling and improving his business plan,” says Paul Davidson, the Pava Center’s associate director. “Jacob started the cohort with strong product and technical experiences, but in order to grow, founders must help customers and investors understand why Heisler can provide the best solutions to their needs.”

Perhaps the program’s biggest benefit was helping Heisler build a team. After the offshoring of semiconductor knowledge decades ago, the last remaining industry professionals in the U.S. are now retiring, leaving an inexperienced workforce to take up the reins. Today, four of Heisler Semiconductor’s employees are Johns Hopkins students. “I’m creating a talent pipeline from Hopkins and other universities to help close the knowledge gap—especially here on the East Coast,” he says.

Davidson agrees. “There is enormous potential in the Baltimore–D.C. region for Jacob’s venture to support government, university, and industry innovation. We look forward to continuing to support his growth.”

“I’m creating a talent pipeline from Hopkins and other universities to help close the knowledge gap—especially here on the East Coast.”—Jacob Heisler

Looking ahead, Heisler Semiconductor is developing its flagship technology: 3D chip stacking. “Most chips today are arranged on a flat, 2D plane,” Heisler explains. “Stacking them vertically allows for smaller devices with greater computing power.” While large manufacturers have invested heavily in this approach, mid- and low-volume producers can’t access it at scale. “That’s the gap we’re trying to fill.”

— ERIN P. LEWIS