Shortly after the 2012 launch of the Hopkins Extreme Materials Institute, founder and director K.T. Ramesh noticed a growing issue: “We were having trouble communicating our results,” he says. The solution, he realized, could be found in a discipline uniquely suited to communicating the abstract: art.

So Ramesh reached out to the Maryland Institute College of Art to create the HEMI/MICA Artist-in-Residence program and an internship program for MICA faculty members and students. The partnership also includes an undergraduate course that culminates in a student exhibition at MICA.

“The idea is to bring in people who talk and think completely different from us,” Ramesh says of the residency, which gives MICA artists access to work in a HEMI lab of their choosing for a year (or a summer, for student interns) to share their perspectives and experiences and create a culminating body of work.

Jay Gould

Inaugural HEMI/MICA Extreme Arts Program

Artist-in-Residence, 2016–17

MICA Faculty, Photography

Dividing Time

Accordion book

What does the fraction of a fraction of a second look like? Or, as Jay Gould, a member of MICA’s photography faculty puts it: How do you embrace the absurd? To test the dynamic stress-strain response of materials, Ramesh’s HEMI lab uses an apparatus known as a Kolsky bar and a high-speed camera, capable of recording 7 million frames per second, to quickly break materials into minute time scales.

The process, equipment, and resulting computer images inspired Gould to create Dividing Time, which Gould describes as a “larger-than-life tribute to 36 microseconds.” The 180-page accordion book narrates an unfathomable time scale, unfolding into exact, sequential photos from the rapid compression of a 2-millimeter piece of magnesium. Like a slow-motion flip book, the pages morph from white images speckled with gray into grainy cross-hatchings filling the margins. When stretched to its full length, it reaches 90 feet.

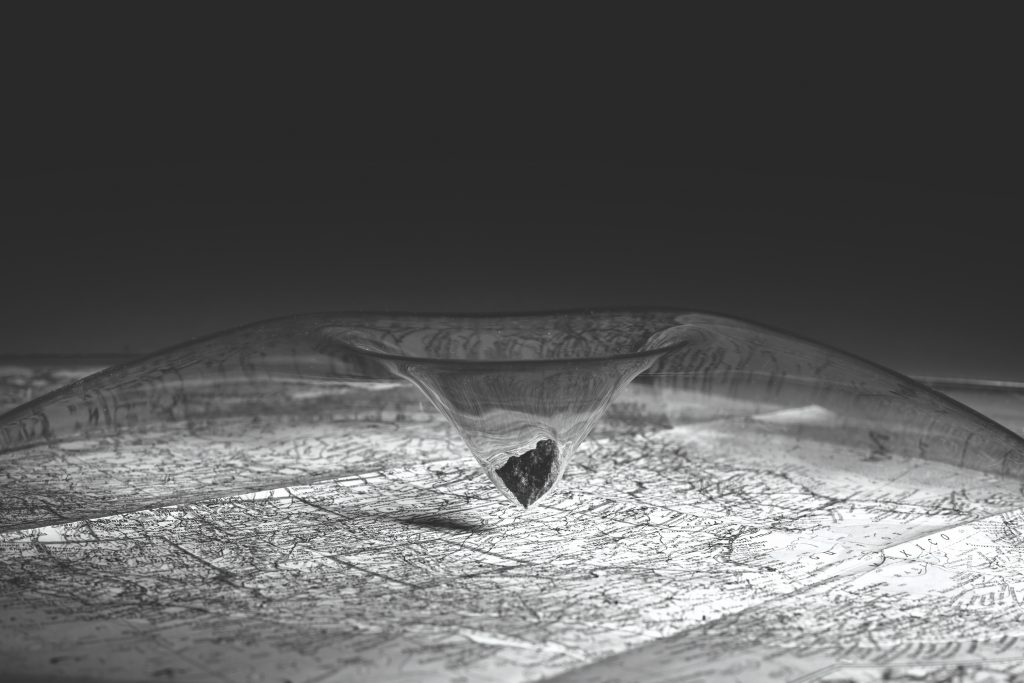

Bolides: Extinction

Bolides: Extinction is another of Gould’s HEMI-inspired works. This 40-inch by 60-inch print is his interpretation of meteorites burning up in Earth’s atmosphere. “I saw a NASA map of bolides [the light emitted by a large meteor as it explodes in the atmosphere] and wanted to depict a meteorite landing in the middle of the continental U.S.,” he explains. “HEMI is all about defense, and my photo is the ultimate defense—but the sci-fi, most exaggerated version.” Using a rock from Ramesh’s lab, Gould pushed it into a heated a sheet of acrylic. Photographing it against a map gave him the ability to dramatically play with scale.

The results stunned Ramesh and his team. “They gasped when I showed it for the first time,” says Gould, who continues to make asteroid-inspired art. “A lot of artists are really interested in science. To have my students see me collaborating with research labs gives them the freedom to embrace collaborations.”

Kim Hall

HEMI/MICA Extreme Arts Program

Artist-in-Residence, 2017–18

MICA Faculty, Illustration Practice MFA

Owner, Nottene Studio

The Curse of Dimensionality

Digitally printed wallpaper and hand-screened curtains

“I’m interested in how small differences can be huge when you try to quantify them,” explains Kim Hall, who teaches illustration at MICA and who connected immediately with work taking place in the lab of HEMI associate director and chair of the Department of Civil Engineering, Lori Graham-Brady. Hall visited the lab each week and sketched while Graham-Brady’s team wrestled with the theoretical complexities of creating multiscale computer modeling of materials with random microstructures.

“I’m interested in how small differences can be huge when you try to quantify them,” explains Kim Hall, who teaches illustration at MICA and who connected immediately with work taking place in the lab of HEMI associate director and chair of the Department of Civil Engineering, Lori Graham-Brady. Hall visited the lab each week and sketched while Graham-Brady’s team wrestled with the theoretical complexities of creating multiscale computer modeling of materials with random microstructures.

“They are trying to figure out things, but the real world complicates it,” Hall explains. “I work with patterns that look at the real world as well.” Hall’s HEMI residency inspired The Curse of Dimensionality. The piece comprises digitally printed curtains with overlapping designs of the Homewood campus’ architecture, as well as digitally printed wallpaper emblazoned with the same Homewood images but interspersed with intellectual “interiors” she experienced during her residency. The interiors included phrases heard in Graham-Brady’s lab and the artist’s spontaneous drawings of equipment, smartphones, and quick sketches of the engineers themselves.

Hall’s exhibition at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library last spring included a materials-inspired interactive component of finished wallpaper that she coated with a white scratch-off paint. During the show’s six-week run, viewers etched their own words, drawings, and symbols into the piece, which Hall says created a deeper connection to her artistic interpretation for viewer, artist, and the engineers with whom she worked.

Hall’s exhibition at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library last spring included a materials-inspired interactive component of finished wallpaper that she coated with a white scratch-off paint. During the show’s six-week run, viewers etched their own words, drawings, and symbols into the piece, which Hall says created a deeper connection to her artistic interpretation for viewer, artist, and the engineers with whom she worked.

“Kim was intrigued by the question of how one might infer important characteristics of a system (such as a material) from only limited information,” Graham-Brady explains of the scratch-off wallpaper. “This is at the heart of what we do in field of uncertainty quantification. We try to take the small amounts of available data to draw meaningful conclusions about how well one can predict the behavior of the problem of interest.”

Amy Wetsch

HEMI/MICA Extreme Arts Program

Student Intern, Summer 2018

MFA ’19, Mount Royal Multidisciplinary Arts Program, MICA

Through the Veil

Mixed media sculpture

Amy Wetsch, an MFA student at MICA, was sure the perfect subject for her HEMI/MICA summer internship would relate to medical research. After all, her artistic focus was on the mysteries of the human body and nature. Then Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, changed her direction.

After talking with Sarah Hörst, a HEMI fellow and assistant professor in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, about her lab’s research on Titan, Wetsch began sketching. Her residency culminated with Lateral Distance, a 10-piece exhibition of drawings and massive sculptural installations meant to immerse viewers in her vision of Titan, that was on display at Baltimore’s Bromo Seltzer Arts Tower last winter.

One of the pieces in the exhibit, Through the Veil, imagines what’s behind Titan’s dense, orange atmospheric haze, composed of complex organics that fall to the moon’s surface. Wetsch crinkled thousands of sheets of iridescent window film into balls to create haze particles that surround the dome that is Wetsch’s imagined essence of Titan. She created the dome’s interior by mixing materials including glue, glycerin, glass, walnut shells, wood, and recycled sand from wind tunnel experiments. To recreate Titan’s rivers of swirling methane and ethane, Wetsch added salt to the mixture, which reacted to the glue to create organic shapes.

Her goal was simple: “When people stand under the dome, I want them to feel the wonder a child has looking up at the night sky.”

Plume

Mixed media sculpture

With Plume, Wetsch’s sculptural interpretation of a mission to Titan, Wetsch explored the “archaeology” of Hörst’s lab via “artifacts”—discarded copper gaskets that were used to seal gas mixtures in the lab’s Planetary Haze Research Chamber. Wetsch filled the gaskets with a mixture of mixed iridescent film, glue, salts, wind tunnel sand, and pigments to create luminous swirling colors.

The sculpture’s base sparkles blue and green, representing Earth, and as the rocket’s trajectory rises, the colors transition to yellow and finally to orange, the color of Titan’s signature haze. Each copper plate is connected by smaller copper rings, an engineering feat enabled by hands-on help from lab members.

“Watching scientists create experiments feels so similar to artists’ problem-solving,” Wetsch says. “To simulate atmosphere, the lab takes gases, puts them into a chamber, adjusts the temperature, and waits for a reaction. It’s what I do when I combine materials and wait to see how they come together.”