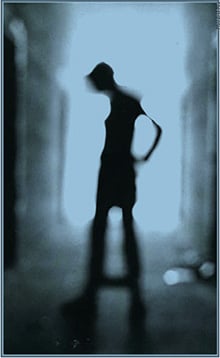

Aaron Chang ’14, a biomedical engineering student, remembers the first time he spoke with a prostitute on a Baltimore street. “There was just this death look in her eyes,” says Chang, a volunteer with Safe House of Hope, a Baltimore nonprofit founded in 2010 to help victims of sex trafficking.

Aaron Chang ’14, a biomedical engineering student, remembers the first time he spoke with a prostitute on a Baltimore street. “There was just this death look in her eyes,” says Chang, a volunteer with Safe House of Hope, a Baltimore nonprofit founded in 2010 to help victims of sex trafficking.

Chang, like other Safe House of Hope volunteers, drives around the Baltimore neighborhoods most known for having sex trafficking victims—those who are coerced into selling sex. The volunteers provide care packages to those on the streets, and rubber bracelets with a 24-hour hotline number for access to health care, legal services, and other resources through Safe House of Hope.

“There was just this death look in her eyes.” Aaron Chang ‘14

Chang, who is originally from Grand Prairie, Texas, says he got involved with Safe House about two years ago because he was chagrined that sex trafficking, which he mistakenly assumed was a problem only in the developing world, was so prevalent in Baltimore, where volunteers have logged 758 encounters with local victims since March 2011.

He stopped volunteering with the program briefly because he doubted he could make a difference, then rejoined in January 2012. This time, he helped create a system that replaced the random notebooks, scraps of paper, and incomplete files that were being used for recordkeeping.

Using Google spreadsheets and analytics, Chang created an online system that makes it easy for volunteers to sign up, keep records of supply donations, track patterns of human trafficking in Baltimore, and measure outreach efforts and services provided. A grant from the Baltimore Collegetown LeaderShape program, funded by PNC Bank and run by the Baltimore Collegetown Network, provides support for Chang’s project.

“It used to be hard for someone to coordinate,” says Denene Yates, executive director and founder of Safe House of Hope. “Aaron just really took on the job of being the student outreach coordinator. He put everything on Google so everybody could sign up. He just organized it all on a dashboard-like system.”

Now volunteers sign up online, and it’s easy for coordinators to see how many people are available on any given night to drive around Baltimore between midnight and 4 a.m., offering packages with food, water, condoms, and the bracelet.

Chang is joined in his volunteer efforts by engineering students Jimmy Lin, Rochelle Dumm, and Allen Jiang, all BME ’14; Austin Jordan, BME ’15; Matt Daum, MechE ’15; and Monica Rex, BME ’16.

The students hope to team with other nongovernmental organizations to reach out to sex trafficking victims in other cities with care packages, resources, and a path out. Rex, who has been volunteering since January, says Chang’s system, “is really universal and could easily be implemented around the country.”

And beyond. Justice Ventures International has expressed interest in using parts of the model for anti-trafficking work in India, says Chang. And he hopes to participate in the newly announced Global Human Trafficking Hotline Network, a data-sharing effort launched with a $3 million grant from Google. That project, he says, “validates our approach of mapping and tracking victims.”

The students are also working to raise awareness on campus. On March 28 and 29, as part of a larger effort of the International Justice Mission, they took turns standing for a total of 27 hours, to represent 27 million “modern day slaves,” says Rex. “These women have dreams,” she says. “They have the same goals that we do.”