It could be the future of education and communication.

Or it could be a dud, albeit a striking one. Such is the promise and peril of any new technology, though what’s currently on display in the bottom level of the Brody Learning Commons certainly has the potential to be a game changer.

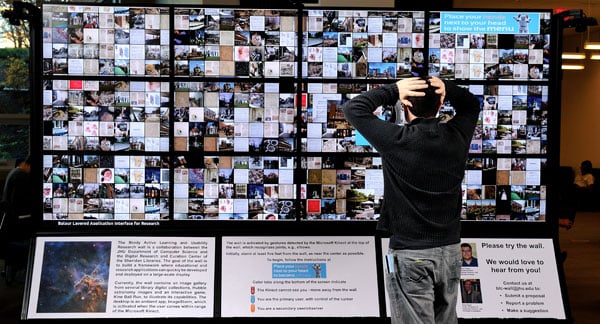

There, residing among a gaggle of studious collegians is a huge video display that, at first glance, could be mistaken for something one might stumble across in the electronics section of Best Buy: row after row of 1080P highdefinition monitors—together measuring 12 feet long and 7 feet high—presenting a collage of eye-catching visuals culled from the Eisenhower Library’s vast digital collections. Of old sheet music, and even older medieval manuscripts. Of iconic Hopkins imagery such as Gilman Hall, and swirling galaxies captured from the Hubble Space Telescope. It’s certainly alluring, this default wallpaper mode of the display.

And yet this doesn’t even begin to hint at how the Balaur Display Wall might change the way students learn, faculty teach, researchers work, and designers collaborate.

For while you are studying the Wall, the Wall is studying you.

Oh, it’s nothing nefarious (well, it could spy, but not in its current state); just three Microsoft Kinect cameras placed on the sides and top of the Wall. Add 55,000 lines of code written by Kel Guerin, a graduate student in Computer Science at the Whiting School, and what you have is a computer/human interface: The Kinects on the Wall triangulate in 3D where you—and others—are standing in front of it and see what parts of you are moving; all that code takes those movements and tells the video display’s computer what action it should take next.

Of course, to set the whole ball of pixels into motion means that first you have to get the Wall’s attention, which in its current state means being willing to look a little silly in public. The Kinect’s cameras are designed to recognize unique physical movements—the kind of gestures not likely to occur when two people are just standing in front of it and talking, so routine hair flipping and toe tapping are out.

Instead, it takes putting your hands to the side of your head—think Munch’s The Scream without the pain—to get the Wall to switch into menu mode. From there, just touch one index finger to the point of the other elbow to turn into a human cursor. It’s a heady experience, allowing you to play Tron-like games, or display pictures where zoom and motion are all controlled by kinetic action: Palms out creates a Google Map–like zoom effect, leaning forward increases a game’s speed, and so on. At first, the whole thing is about as clumsy as dancing with a wooly mammoth, but remember, we’re talking first generation here, and one can imagine that the first rehearsals of Dancing with the Stars weren’t exactly poetry in motion.