Nearly a generation before his triumphant exploits in World War II’s Pacific Theater, Gen. Douglas MacArthur entwined with Johns Hopkins lacrosse history.

Nearly a generation before his triumphant exploits in World War II’s Pacific Theater, Gen. Douglas MacArthur entwined with Johns Hopkins lacrosse history.

MacArthur, then a major general, was asked to serve as president of the United States Olympic Committee for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam. The corncob-pipe-smoking military man would appoint a special committee for lacrosse, sanctioned as a demonstration event for the summer games. (The sport had been an official event in two previous Olympic Games-1904 and 1908-with Canada taking gold on both occasions.)

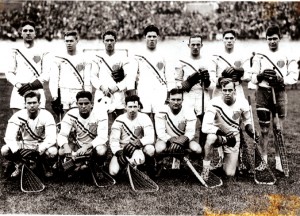

Rather than picking an All-Star team of the country’s best lacrosse players, the committee chose to have an existing team represent the United States. To determine the team, a playoff was set up among six top squads of the day: Johns Hopkins, Army, Navy, Maryland, Rutgers, and the dynastic and heavily favored Mount Washington Lacrosse Club, the equivalent of a professional team today.

On June 9 at Baltimore Stadium, 6th-seeded Johns Hopkins stunned the estimated crowd of 9,000 by downing Mount Washington, 6-4. Hopkins beat Army the following Saturday to advance to the final against the University of Maryland. In that match, played before nearly 12,000 spectators, Johns Hopkins defeated the Terps 6-3.

The historic win punched the Blue Jays’ ticket to Amsterdam to play against New Westminster, the champion of Canada, and the North of England, Great Britain’s representative.

In early July, the squad boarded the S.S. President Roosevelt of the United States Lines, a ship that carried most of the U.S. Olympic team, including MacArthur and swimming great and future Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller. On board, the team stayed in shape with calisthenics and laps around a corklike running track on deck.

Senior second defenseman Robert H. Roy ’28 would later write a chronicle of the trip to Amsterdam and back-a journey filled with banquets, some friendly gambling, a few bouts of seasickness, and lots of elbow rubbing with athletes and VIPs.

Roy, a mechanical engineering major who had overcome a serious injury to his thigh bone his junior year to make the Olympic roster, would go on to a legendary career at Johns Hopkins. He helped establish what would become the Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics and would later serve as School of Engineering dean from 1953 to 1966, and then as dean for engineering sciences until he retired in 1973.

“There can be no doubt that the opinion which most prevailed among our uninitiated was that the players were just there to beat each other up with the sticks.”

from a New York Times aricle about the Olympic Games

In Holland, 40,000 spectators witnessed the first day of lacrosse competition at the Olympic Stadium, where the United States defeated Canada 6-3. As he did in the playoff games, Johns Hopkins coach Ray Van Orman employed tight man-on-man “riding” tactics that featured a glut of stick checking. The physical nature of the game play led to a notable fistfight between center John D. Lang ’30, an electrical engineering major, and the Canadian first attacker, who was perhaps retaliating for another U.S. player’s inadvertently cutting the Canadian player over the eye with his stick. Roy would later note that Gen. MacArthur “raised hell” with the Hopkins players involved.

The lacrosse-unaware Amsterdam press took notice of the defense-heavy sport-which in those days had 12 players per team on the field of play as opposed to today’s 10-person team. “There can be no doubt that the opinion which most prevailed among our uninitiated was that the players were just there to beat each other up with the sticks,” read an article in the June 24 edition of The New York Times, about the Olympic Games.

Roy, in his chronicle, agreed with the summation. “To more than a few of [the spectators], lacrosse was viewed as a kind of genteel murder.”

The Johns Hopkins Olympic team would lose to Great Britain 7-6 the next day. With Canada defeating the British squad on the competition’s final day, a three-way tie arose. Although each team won once and scored 12 goals, Johns Hopkins was named the victor due to the greater goal differential. Coach Van Orman, speaking to the Johns Hopkins News-Letter upon returning to the States, said that the team acquitted itself well on the trans-Atlantic trip, both on and off the field.

“MacArthur and others unknown to me said that the Johns Hopkins team was the most mannerly and the most attractive group of fellows on board the boat. Even in Paris…the boys were easily controlled.” Much credit was given to team captain Carroll “Lefty” Liebensperger, who kept teammates in line.

Lacrosse supporters attempted to make the sport a medal event for the 1932 Summer Olympics, to be held in Los Angeles, but ended up having to settle for a demonstration event.

Once again a playoff would determine the U.S. representative, but this time eight teams were chosen: Johns Hopkins, Army, Navy, St. John’s College, University of Maryland, Mount Washington, Rutgers, and an all-star team of Six Nations Indians, a somewhat controversial pick. Johns Hopkins, undefeated in the regular season, would beat St. John’s and Rutgers to advance to the rematch with the University of Maryland. Hopkins prevailed again.

In Los Angeles, nearly 80,000 were on hand to watch Johns Hopkins defeat Canada in the opening game at the Olympic Stadium on August 7, although lacrosse wasn’t exactly top of the menu.

“The majority were there for the track and field events scheduled for that day,” said Joe Finn, an archivist with U.S. Lacrosse, the sport’s governing body. “The lacrosse game was more an appetizer.” As further evidence of the lacrosse game’s second-class status, officials had to suspend play in the second half to allow for the finish of the Olympic marathon.

Canada won the second match, but Hopkins took the rubber game to capture the unofficial Olympic title. Will Rogers, the famous cowboy, humorist, and vaudeville star, provided play-by-play commentary for the first half.

The 1932 competition featured second defenseman Millard T. Lang ’34, an electrical engineering student and multisport athlete who would go on to a decorated professional soccer career. His field exploits would earn him spots in the National Soccer Hall of Fame, the National Lacrosse Hall of Fame, and Sports Illustrated’s list of top 50 greatest sports figures of the 20th century from Maryland.