Sarah Webster has come a long way since “Marco Polo” meant a swimming pool full of shrieking children. Back then, echolocation was merely the pretext for a game. Today, the mechanical engineering PhD candidate uses underwater acoustic modems, applying the concept to guide robotic underwater vehicles during surveys of the ocean floor and then back to a ship on the surface. There, scientists await the data collected by the crafts—known as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs)— which they use to map the ocean floor, document the discovery of new species, and investigate ocean chemistry in their search for insights to global climate change.

“We need a way to accurately know where the vehicle is in order to make the data useful to the scientists, and so we can return to a site of interest,” says Webster. Because global positioning system signals don’t travel through water, Webster’s work relies on acoustics, instead. “Historically you have several acoustic beacons at known locations and the vehicle sends out a ping, ‘Marco,’” she says, “and the beacons respond, ‘Polo.’” Measuring the elapsed time of that call and response, engineers can triangulate the exact position of the AUV and, over time, its trajectory.

Since she came to Hopkins in September 2004, Webster has worked with her advisor, Professor Louis Whitcomb, and University of Michigan ocean engineer Ryan Eustice to develop techniques to replace multiple beacons on the sea floor with a single beacon mounted on the surface ship; they’ve also introduced modems to transmit rich packets of data containing time and depth information to replace the simple tone signals used in previous decades. Together, their innovations reduce mission costs and allow for the use of multiple underwater vehicles to cover broader territories at sea. While Webster has traveled to both the Atlantic and Pacific, she is grateful that much of the testing happens in the Hydrodynamics Testing Facility in Whitcomb’s Krieger Hall laboratory. Says Webster: “It’s climate-controlled, you can go get a coffee, and come in on the weekend.”

(Photos by Catherine Offinger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

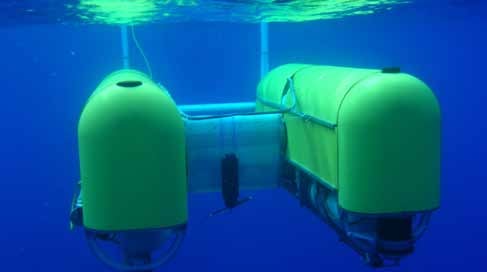

Last May, Webster and Whitcomb departed Guam on a 14-day expedition with two dozen other engineers and scientists from the University of Hawaii, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, and the University of Sydney—as well as a camera crew from the Discovery Channel—aboard the research vessel Kilo Moana. On June 2, as the Kilo Moana hovered nearly 7 miles above the Mariana Trench, Nereus, a hybrid remotely operated vehicle, reached Challenger Deep, the deepest place in the world. The historic 26-hour dive included 10 hours of data collection and a 16-hour round-trip voyage. In addition to providing a live video broadcast back to the ship during the dive, Nereus returned to the surface with samples of rocks, sediment, volcanic fluids, and the life forms that thrive where the Pacific Plate slides below the Mariana Plate—all clues in the quest to understand the dynamic relationship between biological and geological processes.

“The immediate big win is data in real time from a vehicle 10 kilometers below the surface,” says Webster, who was at the control desk for launch and ascent. During all of the dives to the Mariana Trench, the vehicle was connected to the ship by a tiny fiber-optic microcable, which was cut by the vehicle before its ascent. To rejoin Nereus and the Kilo Moana on the surface—without crashing the $8 million craft into the ship or losing it at sea—the scientists relied solely on acoustic data transmissions to estimate Nereus’ position in the water column.

While the mission included eight dives, only one ascent proved truly nerve-racking. When the modem on the ship stopped receiving detailed data packets, the team was limited to using simple sound signals to calculate the horizontal distance between the craft and the ship. A senior scientist from Woods Hole, an expert in earlier navigation techniques, stepped up, and Webster stationed herself at his elbow. “I just ‘went to navigation school,’” she says of the impromptu lesson. “I can imagine putting that to use later on and maybe surprising future grad students who have never seen the old-fashioned, low-tech version.”

Photos: As a graduate student in mechanical engineering,Sarah Webster (above) helped develop the navigation and control system used to guide the autonomous underwater vehicle, Nereus (top) on its voyage to the depths of the Mariana Trench. She’s seen here aboard the R/V Kilo Moana, which served as Nereus’ launching point and command center for the team of scientists and engineers who led the May 2009 expedition.

Photos by Catherine Offinger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution