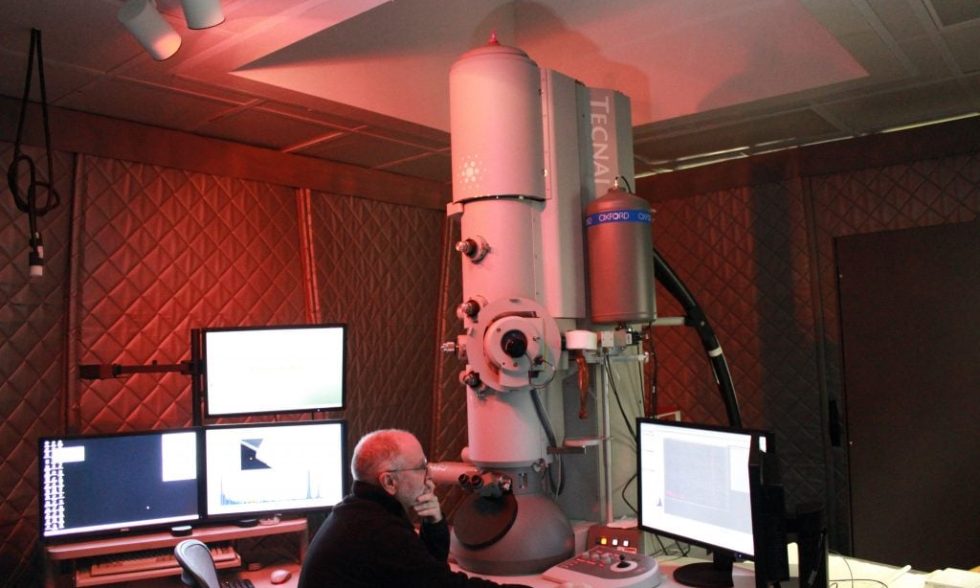

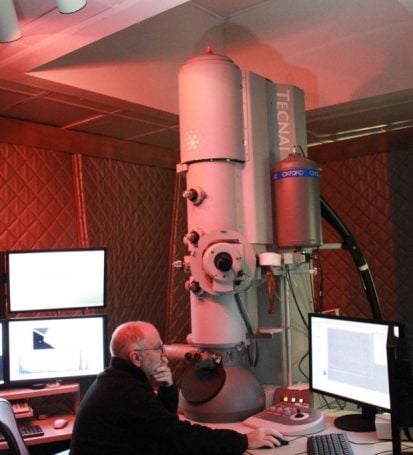

During the Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica in 1911, British geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor made a shocking discovery at the base of the glacier that now bears his name: a waterfall that appeared to be blood. Discharged from beneath the ice, the water emerges clear but then quickly turns crimson. This phenomenon, which Taylor dubbed Blood Falls, has captured people’s imaginations and, until now, remained a scientific mystery. Using powerful transmission electron microscopes at Johns Hopkins’ Materials Characterization and Processing facility, Ken Livi, a research scientist in the Whiting School’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, examined samples of Blood Falls’ water and found tiny, iron-rich nanospheres. These round solids are 100th the size of the human red blood cell and nave unique physical and chemical characteristics, including turning red when they oxidize. To understand this long-standing Blood Falls mystery, you must first understand Antarctic microbiology, Livi says. “There are microorganisms that have been existing for potentially millions of years underneath the saline waters of the Antarctic glacier,” he says. Scientists believe that this unusual environment could contribute to the search for life on other planets. That’s how Livi, an expert in planetary materials, came to this project, which he worked on as part of a team with experts from other institutions. Their results appeared in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences. “With the advent of the Mars rover missions, there was an interest in trying to analyze the solids that came out of the waters of Blood Falls, as if it was a Martian landing site,” he explains. “What would happen if a Mars rover landed in Antarctica? Would it be able to determine what was causing the Blood Falls to be red?” Their research showed that analysis by rover vehicles wouldn’t work on a planet, like Mars, “where the materials formed may be nanosize and noncrystalline,” Live says. “To truly understand the nature of rocky planets’ surfaces, a transmission electron microscope would be necessary, but it is currently not feasible to place one on Mars.”

During the Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica in 1911, British geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor made a shocking discovery at the base of the glacier that now bears his name: a waterfall that appeared to be blood. Discharged from beneath the ice, the water emerges clear but then quickly turns crimson. This phenomenon, which Taylor dubbed Blood Falls, has captured people’s imaginations and, until now, remained a scientific mystery. Using powerful transmission electron microscopes at Johns Hopkins’ Materials Characterization and Processing facility, Ken Livi, a research scientist in the Whiting School’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, examined samples of Blood Falls’ water and found tiny, iron-rich nanospheres. These round solids are 100th the size of the human red blood cell and nave unique physical and chemical characteristics, including turning red when they oxidize. To understand this long-standing Blood Falls mystery, you must first understand Antarctic microbiology, Livi says. “There are microorganisms that have been existing for potentially millions of years underneath the saline waters of the Antarctic glacier,” he says. Scientists believe that this unusual environment could contribute to the search for life on other planets. That’s how Livi, an expert in planetary materials, came to this project, which he worked on as part of a team with experts from other institutions. Their results appeared in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences. “With the advent of the Mars rover missions, there was an interest in trying to analyze the solids that came out of the waters of Blood Falls, as if it was a Martian landing site,” he explains. “What would happen if a Mars rover landed in Antarctica? Would it be able to determine what was causing the Blood Falls to be red?” Their research showed that analysis by rover vehicles wouldn’t work on a planet, like Mars, “where the materials formed may be nanosize and noncrystalline,” Live says. “To truly understand the nature of rocky planets’ surfaces, a transmission electron microscope would be necessary, but it is currently not feasible to place one on Mars.”